|

| History of

Slavery Gardens

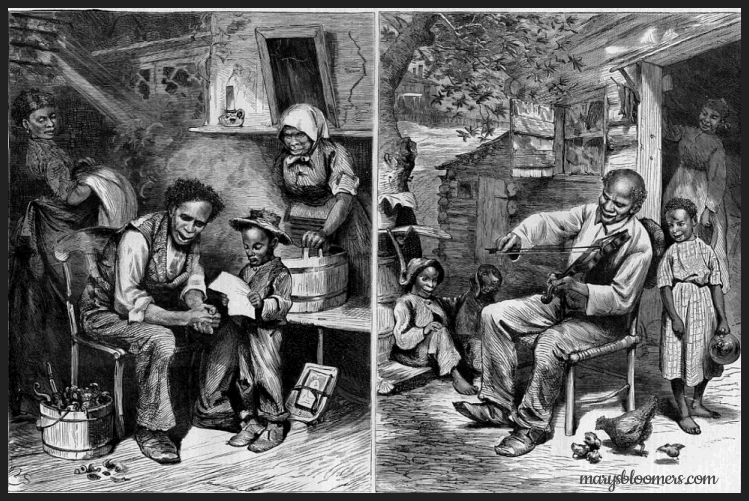

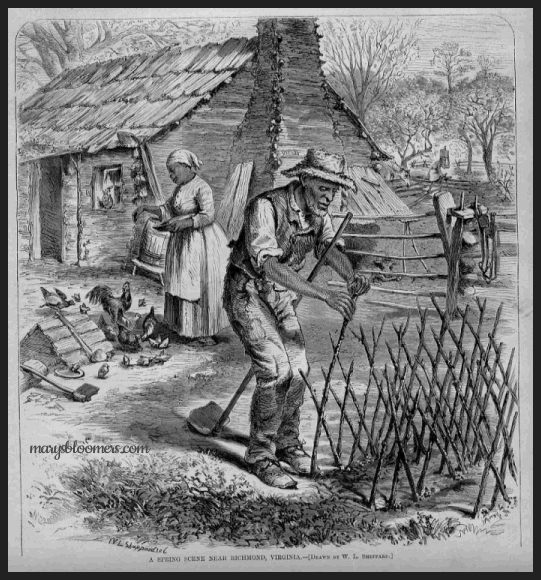

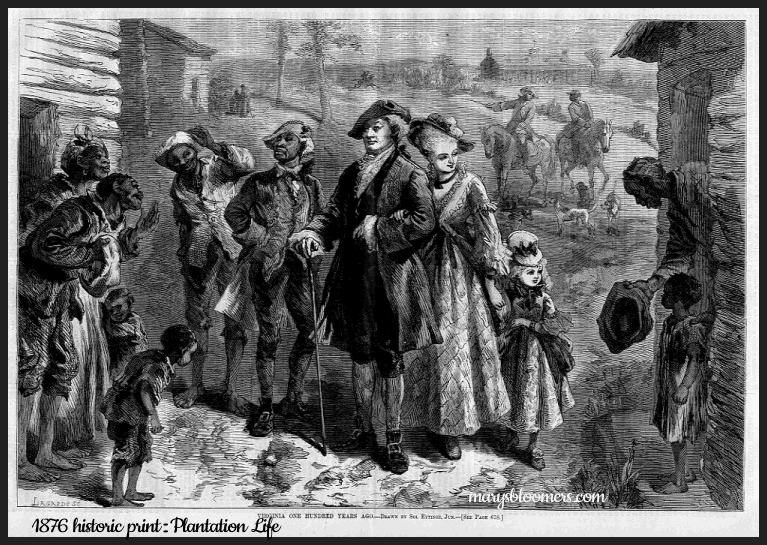

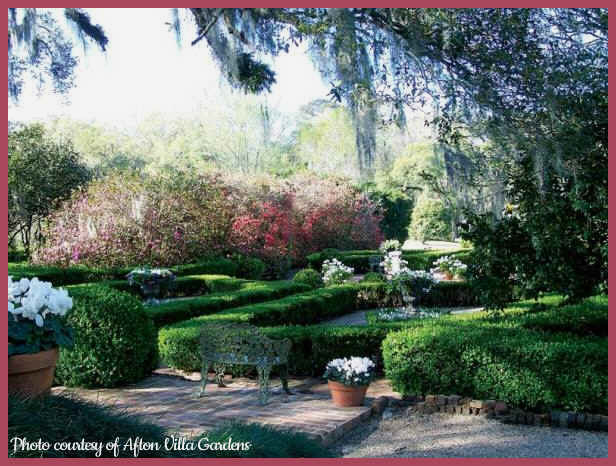

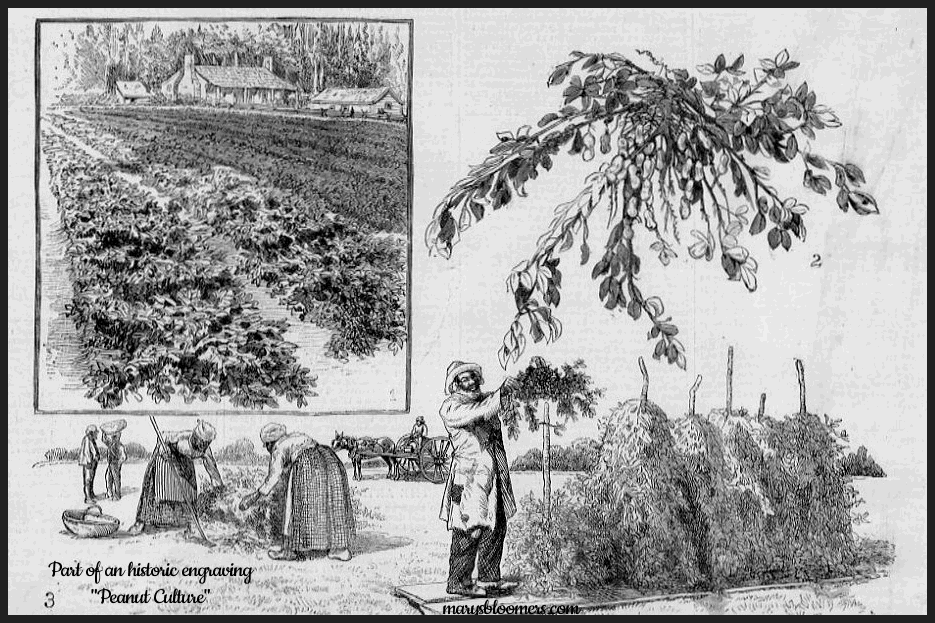

Antebellum and Slavery Gardens - Ornamental Landscapes of the rich, and the Slave Gardens sustaining the health of the enslaved people who made them rich, and drove the southern economy. What we see as we travel in the southern states of the U.S.....Elaborate flower gardens of plantation owners tended to be designed in a geometric manner that complemented the classical and formal lines of the house. During the antebellum period (approximately 1812 to1860), Greek Revival, Classical Revival, and Federal-style homes were very much the style of the day - imposing, grand estates that were symmetrical and box-like, with central entrances ornamented with stately columns. Magnificent climbing roses, rows of azaleas, camellias and gardenias that graced arches, gazebos, and landscape summer houses. To understand and design the Slave Food Garden as an ancestral garden theme, we need to look upon history and the African slave cultures first... the contrast between the human trafficking of people kidnapped from another continent, auctioned, and kept as slaves, and the wealthy, but sub-human culture that bought and sold them. Ethnic food history and the cultures who created them are important if we are to learn from this dark history, and preserve the customs, foods and recipes associated with them. The slavery atrocity left us such culinary legacies as Soul Food, Cajun, Creole, and many other cuisines. Descendants of slaves have created African American Heritage food gardens based on the culinary treasures and customs left to them by their enslaved ancestors.

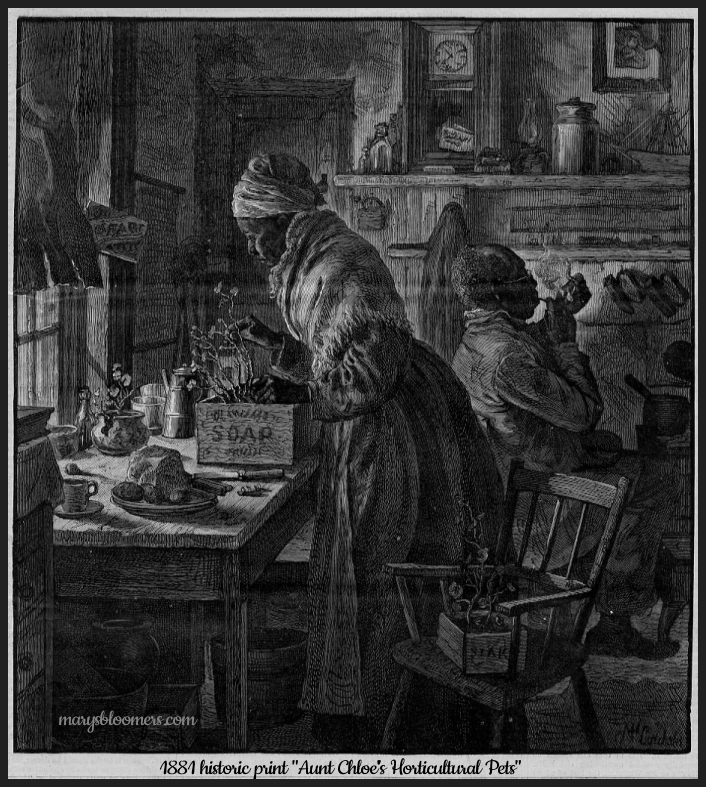

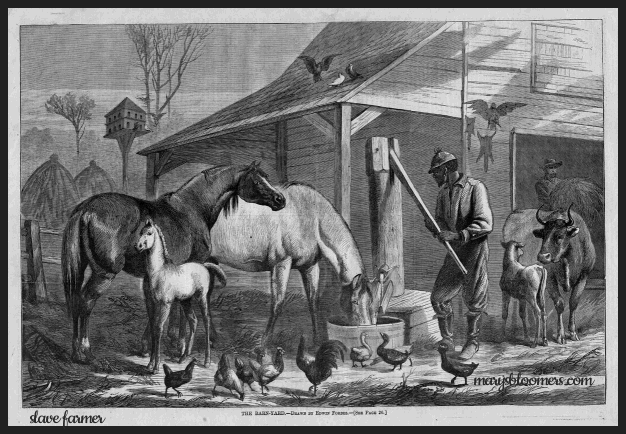

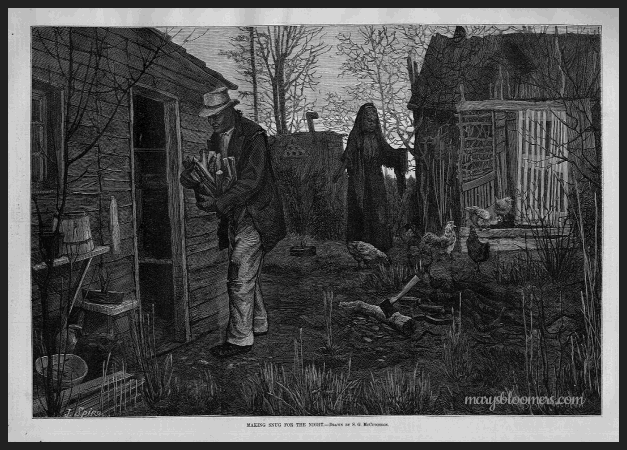

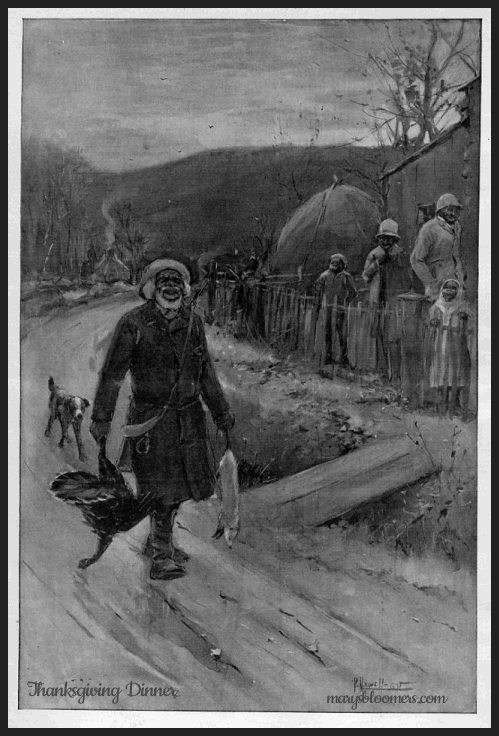

I will soon be writing about the lovely ornamental gardens in the southern U.S, along with how and what to plant to create your own, but for now, I'm concentrating on the garden's connection to a culture, and vice versa, rather than just the eye-popping beauty of gardens on a tourist maps of the deep South. I love visiting and living in the south.... I am not anti-southern-states. And I love southern American cuisine. But when I look at an historic garden in my travels, I visualize the people and cultures who grew them. Most likely than not, the people who planted, grew and harvested crops and cared for gardens of the wealthy were of the lower classes, or those in some type of human bondage. The Medieval European Peasant Gardens were also an example, although not steeped in the historic cruelty that formed the basis and the need for Slavery Gardens. Slave Gardens were grown for survival. Timeline: 1619-1865 Gardens of Slavery Hidden from view at the “back of the big house” on plantations or behind the manors of the wealthy, the gardens created by African American slaves in the U.S. are an important part of garden history. In addition to tending the crops of slave owners, many African Americans found the time to cultivate their own garden plots. These gardens provided additional food to the enslaved community and sometimes yielded enough produce to sell for profit. Some slaves were permitted to sell their fresh produce to wealthy white folk. Some were known as the "chicken merchants" of the south. Those who fished the coastal areas were known as "fish merchants". Those resourceful slaves knew how to grow things and did the work required to put fresh food on a plate, especially when fresh produce was impossible for the rich to acquire in winter - like preserving crops, and fishing nearby waterways - that the wealthy did not or could not do. These slaves were considered privileged. They were paid a meager amount of money that could be used to buy their freedom, purchase food and medicines, and purchase a few chickens and small livestock to supplement their rations. The Slave Garden (Huck Patch)Slavery certainly didn't begin with the Civil War era American slaves. It was a global and multi-era abomination. Almost every country's history has included trafficking in human beings. But none was as brutal as slavery in America, which eventually sparked a bloody civil war, and when The United States was not the slightest bit united in their views about human ownership and bondage. Occasionally, 18th century slave owners allowed their workers to lay out and plant small gardens to supplement the usually meager food provisions allocated to the field slaves. Some masters intentionally delegated a small plot of ground for this purpose near the slave quarters. Slaves would prepare their garden plots after sundown and on Sundays when most had a lighter work schedule.

The problems with planting and harvesting herbs and vegetables were something the slaves knew well, since they planted and maintained the gardens of their masters. They would save the seeds for annual plants, just as they did for their masters year to year. The wealthy landowner would have his slaves build a wall or intricate fence around his plantation's kitchen garden to keep deer and other trespassers out, and his slaves would need to find a way to do the same for their little gardens. Permitting slaves to independently raise produce, and even livestock, was not new in the 18C Chesapeake, Virginia. Since the 17th century, some masters had allowed their slaves to grow tobacco, corn, horses, hogs, and cattle and to sell them to gain enough money to buy their freedom and the freedom of their wives and children. Sensing that this was a serious threat to their labor pool, in 1692, the Virginia General Assembly ordered slave owners to confiscate "all horses, cattle and hoggs marked of any Negro or other slaves marked, or by any slave kept." The practice of allowing independent garden plots had begun again during the first half of the 18C.

What was grown in the

historic Slave Garden: Cimnells were small squash. In

addition to field peas and squash, slaves also planted potatoes, beans,

onions, and collards. All these crops could be eaten raw, boiled in a

pot, or roasted on the coals of a small fire. Over winter, the slaves

could store some of their produce inconspicuously in the ground, saving

them for themselves, just like they did for the master. Slave owners knew they could

learn about both life and gardening from their enslaved servants.

About twenty years later, it was written that "Adjoining their little habitations, the slaves commonly have small gardens and yards for poultry, which are all their own property… their gardens are generally found well stocked, and their flocks of poultry numerous." If the master allowed his slaves to keep poultry, the slave not only took advantage of the extra food, but also sold some of the chickens for extra spending money. The director of the shameful slave-owner/president (my words) Thomas Jefferson's gardens and grounds at Monticello, reported that "Jefferson's Memorandum Books, which detailed virtually every financial transaction that he engaged in between 1769 and 1826, as well as the account ledger kept by his granddaughter, Anne Cary Randolph, between 1805 and 1808, document hundreds of transactions involving the purchase of produce from Monticello slaves." A paid slave is still a slave. The

records show the purchase of 22 species of fruits and vegetables from as

many as 43 different individuals..."much of the produce purchased

from Monticello slaves was out of season: potatoes were sold in December

and February, hominy beans and apples purchased in April, and cucumbers

bought in January. Archaeological excavations of slave cabins at

Monticello indicate the widespread presence of root cellars, which not

only served as secret hiding places, but surely as repositories for root

crops and other vegetables amenable to cool, dark storage.

Throughout most of the 18th century, indentured white servants, and free and enslaved blacks were the backbone of the garden labor force in the Mid-Atlantic and Upper South. While free white professional gardeners and nurserymen began to appear after the Revolution in the urban areas, it is likely that until the Civil War, most Mid-Atlantic and Upper South gardens, and the pleasure gardens in Maryland, were maintained by black gardeners, some of them free, but most of them slaves. Ornamental

Plantation Gardens vs. Slave Gardens One is a glorious treat for the eyes, and the other helped to sustained the health and lengthen the lives of mistreated slaves who tended those big gardens. On a working plantation, the decorative garden was usually front and center and sometimes wrapped to the sides of the house, but the rear was reserved for more functional uses, like outbuildings for servants’ quarters, cooking, and kitchen gardens. In rural areas, visitors would approach the house and front garden via an avenue of live oak tress, with their stately, curving branches, dripping with Spanish moss, these trees were a ceremonial entrance to the plantation, focusing attention on the house itself. Plantation gardens were usually parterres, which were formal gardens of planting

beds that were edged in patterns of clipped and shaped boxwood shrubs

and symmetrical gravel, sand, brick or crushed-seashell paths.

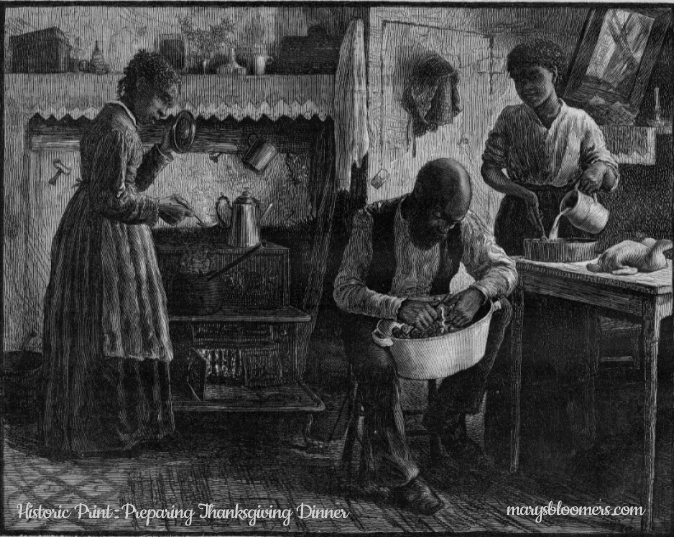

All across the South, massive, ornate plantation homes were constructed with money generated through a slave-driven economy. As in other cultures, the enslaved turned to the garden for food and spiritual uplifting. Some of the most beautiful southern gardens and plantations were kept and grown by the slave, while the wealthy had parties and showed off their beautiful gardens, of which they had no part in planting, growing, or nurturing. The slaves were not permitted to revel in the beauty and bounty of such elaborate gardens. They grew little gardens for food in order to stay alive. The wealthy plantation owners wanted them healthy, because a healthy slave is a working slave. Someone had to pick and move the cotton and other crops that the rich grew richer from. Slaves were given "garbage" food from the big house's kitchens, and kitchen scraps to eat, or to take home to their families. The owner's dogs ate better. They sometimes got permission to grow a food garden on their tiny plots of land that didn't actually belong to them, developed their own cuisines from these meager scraps and whatever meats and fishes they could find, depending upon which southern state they inhabited, and the cuisine depended upon which country they were stolen from. They lived in extreme poverty, in close quarters and horrible living conditions, had no land or money, but they did preserve their pre-slavery heritage and created the beloved soul food, creole, cajun and gullah/geechee cuisines that we seek out when we travel through the deep south.

I love the ornate and sometimes gaudy, ostentatious plantation gardens and those of the manor, and I view these as eye candy and a place to generate my ideas of garden design and growing new plants. But slave gardens stand for something deeper and real. Simple and lovingly tended, the food gardens kept the slaves healthy and alive. At harvest, they turned what they could grow into something quite sustaining and delicious, food was preserved for the cold months, and the created meals were comforting, fairly healthy, filling, and unique to the culture. The slave gardens represented survival and hope.

To read about the origins of Soul Food cuisine and how to grow a Soul Food vegetable garden, visit this page. To read about designing an African American Heritage Garden, visit this page. To learn about peasant gardens in Medieval Europe, and the lives of serfs and peasants, click here. To view creole and cajun garden themes, click here.

Article ©2021 Mary Hyland Sources for the compilation of this article:

Design, graphics,

articles and

photos ©2020 marysbloomers.com™ |