| Garden History -

Peasant Vegetable and Flower Gardens- The dawn of the beloved Cottage

Garden in England

"Gardening is for

peasants" - That was the common refrain of the uber rich uber

snobby upper classes. Those rich folks worshipped the lawn. This

religion came in handy for those who were privileged and lazy, and did

nothing all day but admire the green expanse of nothingness outside

their mansions and castles, which they never tended themselves, crowing

about their croquet and tennis courts, and hosted big outdoor luncheons

upon them. If there was a garden somewhere out there, you can be assured

that the serfs and peasants took care of it. Sometimes, a Lady in the

manor had a love of growing things, and when all efforts to prevent her

from getting medieval soil under her manicured fingernails failed to

deter her, she could be found lovingly tending a garden, which was most

likely out of view of the rest of the upper class family and friends,

and was not to be seen from the street or from within, through the

windows. Thankfully, the medieval peasants and serfs didn't mind being

the inventors and curators of the beautifully disorganized and

beautifully scented English Cottage Garden.

Among all the horticultural

contributions made by the nation of impassioned gardeners, none may be

so influential and charming as the humble English

cottage garden. Appearing as if it sprung naturally from the

earth, the cottage garden

is an impressionistic work of art, and a riot of scent and color.

The

gardens of the middle and upper classes were formal, sometimes almost

flowerless, at other times filled with the most exotic annuals. It was

the peasant plots in Medieval England that often provided the only

refuge for plants that were virtually discarded by affluent, fickle

gardeners.

The

English cottage garden was free-form by nature, rejecting straight lines

and neat beds, it employs certain elements that have become its

hallmarks: fragrant roses over an arched doorway, the scent of

rosemary outside the kitchen window, the seemingly wild tangle of

poppies and hollyhocks that spill over onto well-worn old stone paths.

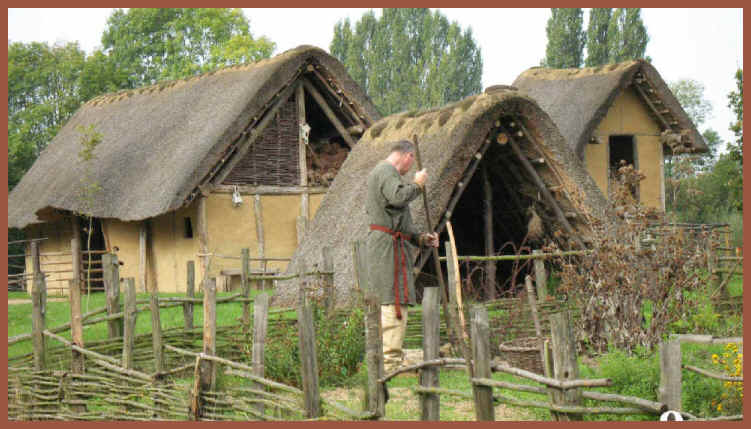

Today,

the charming ''artlessness'' of the English garden is often carefully

planned by landscape architects. But the rustics who first planted them

had no intention of creating an international fashion in gardening. They

simply constructed the most traditional shelter they could afford, and

surrounded it with a wide range of hardy perennials that could survive

the English winters.

Medieval

Peasantry

It wasn't called The Dark Ages for nothing.

Serfs were peasant farmers who were neither fully free, nor were theyslaves.

They could not leave the village, sell an ox, or marry without the lord

of the manor's permissions. The peasants had a little more freedom but

still rarely left their local area. According to the law, serfs did not

belong to themselves. They and all their belongings, their house,

clothes, and even their food, were owned by the lord of the manor. They

were bound to work for their lord, who allowed them to farm their own

piece of land in return. Their lives were ones of constant toil. Most

struggled to produce enough food for their own families as well as

fulfilling their duties to the lord of the manor. Life expectancy of the

serfs was 27 years.

For centuries, serfs (real meaning:

slaves) had worked the land belonging to great lords. Suddenly, the

Black Death of 1349 nearly wiped out the population. In England, more

than one-third of the population died, and only a tiny proportion of the

rural labor force survived. The great imbalance of supply and demand for

manual labor gave the serfs an opportunity to put a premium on their

services. Many serfs were allowed to take over vacant land and

they became remarkably liberated as tenant farmers.

Peasant

Practicalities

Soon afterwards, gardens began to appear around their cottages of stone

and wood and thatch. These were used at first for practical plantings:

vegetables and herbs. Peasants rarely had or ate meat; so plants

provided most of their nourishment. Herbs were not only an inexpensive

source of seasoning, but also an important source of medicine.

Peasants

might stop along the lane on their way home from work and dig up a

wildflower for their home gardens. This marked the beginnings of the

cottage wildflower garden... Hybrids were created by mere chance. Botanical

oddities were revered as treasures, pried loose from soil and between

stones by hand, tucked into a pocket, and carried home to be set among

the vegetables and herbs. Little by little, the peasant garden became a

place of delightful disorder, a green cabbage growing with cabbage

roses, daffodils surrounded by onions and marigolds, and so on.

Cottage

Gardens

An

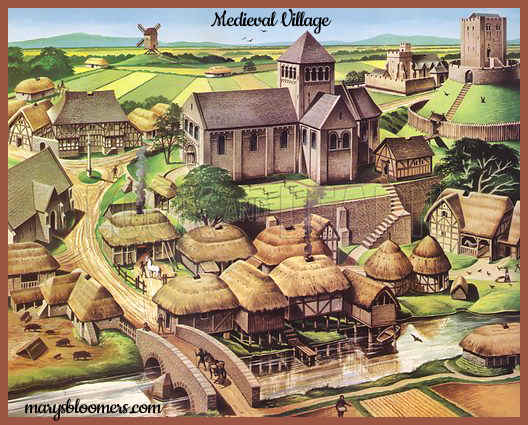

enclosed yard with a stone wall or wood fence separated the garden from

the main village road. A straight path led from this lane to the front

door. This walk was edged with herbs, and behind them were

vegetables-arranged for easy access. A few fruit trees and perhaps a

beehive completed the basic plan.

As

the cottage garden became more and more sophisticated, vegetables and

fruit were restricted to a separate site. In many instances, tall

hollyhocks, foxgloves and delphinium backed the flower borders and

shielded the homely vegetable plots from view from the sitting-room

windows of the cottage.

By

the 16th Century, increased commerce overseas helped to introduce many

new flowers to English soil. Huguenots, fleeing persecution in France,

brought many flowers, such as auricula (a species of primrose) and

dogtooth violet (Erythronium).

From

the early 17th Century on, many plants began to arrive from the

Americas. A gardener named John Tradescant introduced to England the

spiderwort (Tradescantia) and many blue asters. The wilds of Canada were

the source of several goldenrods and rudbeckia (blackeyed susan).

These valuable introductions greatly extended the growing season of the

English garden.

By

the 18th Century, the English cottage gardens contrasted greatly with

the meager gardens of the French peasants, which consisted almost

entirely of apples and cabbages.

In

1500 there were perhaps 200 kinds of cultivated plants in England. By

1850 the varieties had reached 18,000.

Nearly all garden flowers of today were the glories of these fertile

years of the cottage garden. The triumphant naturalized landscapes so

fashionable today are the offspring of those rustic little plots of

cabbages, herbs and flowers invented by English peasants.

These

rustic landscapes were so slightly appreciated in industrial Britain

that they barely survived the 19th Century. The old-fashioned hardy

perennials of the cottage garden were fast losing popularity with

townspeople who wanted to imitate the upper classes and plant the most

flamboyant and gaudy annuals.

Those

who had profited greatly from the Industrial Revolution wanted broad,

expansive lawns around their homes, which they felt gave their estates a

grandness representing wealth and refinement. The last thing the rich

wanted in 19th Century England was a peasant`s garden.

In

1889. a partnership set a style that became known as the ''Surrey

School,'' in essence, an approach to landscaping that emphasized

harmonious arrangement of informal gardens within formal structures-the

very epitome of the gardening trends most respected today.

Plants

Grown In The Peasant Cottager's Garden

Essentially there were 4 types of

plant in a medieval peasant garden. Vegetables, herbs, flowers and

fruit. Peasants grew all the herbs we know today, plus many more since

forgotten. Some flowers were grown for ornamental use, others for

salads and medicinal potions. The most common fruit was apples, pears,

quince, rhubarb and elderberry.

An example of a peasant food

garden design is the French Potager

Garden (kitchen vegetable garden). Download the design

and layout, free.

Authentic gardens of the yeoman

cottager would have included a beehive and livestock, and frequently a

pig and sty, along with a well. The peasant cottager of medieval times

was more interested in meat than flowers, with herbs grown for medicinal

use and cooking, rather than for their beauty. By Elizabethan times,

there was more prosperity, and more room to grow flowers. Even the early

cottage garden flowers typically had their practical use—violets were

spread on the floor (for their pleasant scent and keeping out vermin);

calendulas and primroses were both attractive and used in cooking.

Others, such as sweet william and hollyhocks, were grown entirely for

their beauty.

Until the late 19th century, cottage

gardens mainly grew vegetables for household consumption. Typically half

the garden would be used for cultivating potatoes and half for a mix of

other vegetables plus some culinary and medicinal herbs.

John Claudius Loudon wrote

extensively on cottage gardens in his book An Encyclopædia of

Gardening (1822) and in Gardener's Magazine from 1826. In

1838 he wrote "I seldom observe any thing in a cottage garden but

potatoes, cabbages, beans, and French beans; in a few instances onions

and parsneps, and very seldom a few peas". An 1865 issue of The

Farmer's Magazine noted that in "Ireland and much of the

Highlands of Scotland, potatoes are the only thing grown in the

cottage-garden".

A few plants that were historically grown and wildcrafted by the

medieval under-classes for food, ornamental purposes, medicine, and magic

- Angelica

- Blessed Thistle

- Catmint

- Chickweed

- Chicory

- Chives

- Comfrey

- Cowslip

- Dill

- Foxglove

- Fennel

- Good King Henry

- Horehound

- Lady's Mantle

|

- Lemon Balm

- Mints

- Mugwort

- Mullein

- Nettles

- Oregano

- Poppies

- Soapwort

- Sorrel

- Tansy

- Thyme

- Vervain

- Wormwood

- Yarrow

|

Gardens

of The Medieval Peasantry

| The

"kitchen garden" was where some vegetables and herbs

might be grown for food, as well as for fuel or as habitat for

animals which were hunted. The "physic garden" would

be planted with various medicinal herbs. The "aesthetic

garden" was developed largely for ornament and pleasure.

Many times a gardener would use a plot of ground for a mixture

of the recreational, aesthetic, and practical purposes. Flowers

in a garden with their fragrance would be both practical and

aesthetic. Medieval gardens were frequently enclosed; the

fragrances of flowers and herbs were confined and concentrated. |

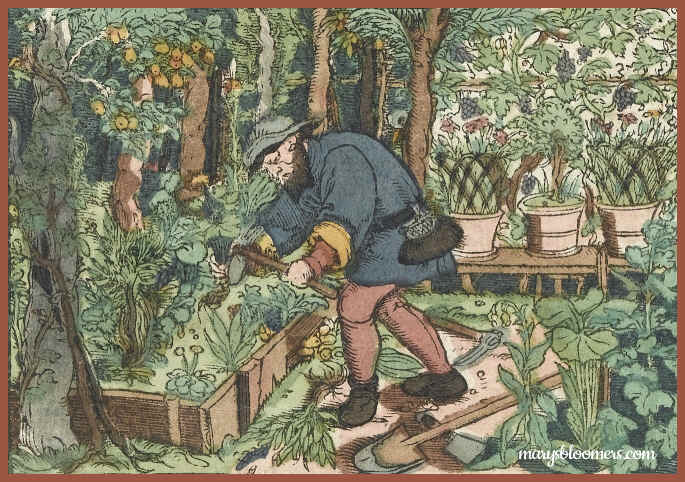

The

tasks of the peasant in tending a garden

Spring

Spring was the time to sow seeds and nurture plants and bulbs

from the previous year. There were no chemical fertilizers, so nitrogen

had to be found growing naturally, then used as a tilled-in amendment.

Usually, this took the form of manure. "Muck spreading",

as it’s commonly known in England, dates back at least 8,000 years.

Summer

As summer approached, the peasant garden was at its best.

Flowers were blooming, herbs, fruit and vegetables all thriving. Peasant

gardeners had to ensure the soil was not too dry, and most peasant

gardens had their own well. If not, they had were usually close a stream

or river because water was a prime factor in good garden

‘housekeeping’

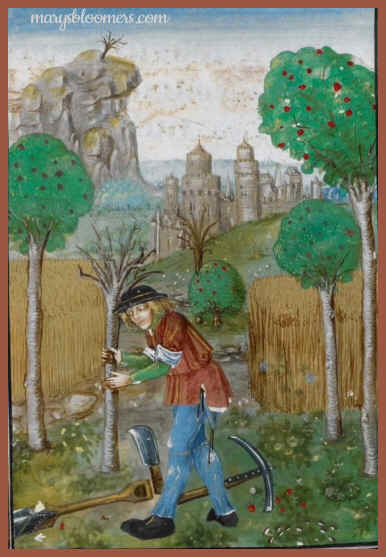

Autumn and Winter

Autumn was the time for harvesting. Tasks were varied, and involved

picking fruit from trees, gathering herbs and flowers, and uprooting

garden root vegetables. As winter approached, peasants spent much of

their time preserving fruits and vegetables to make storable sources of

nutrition.

The

Peasant’s Diet

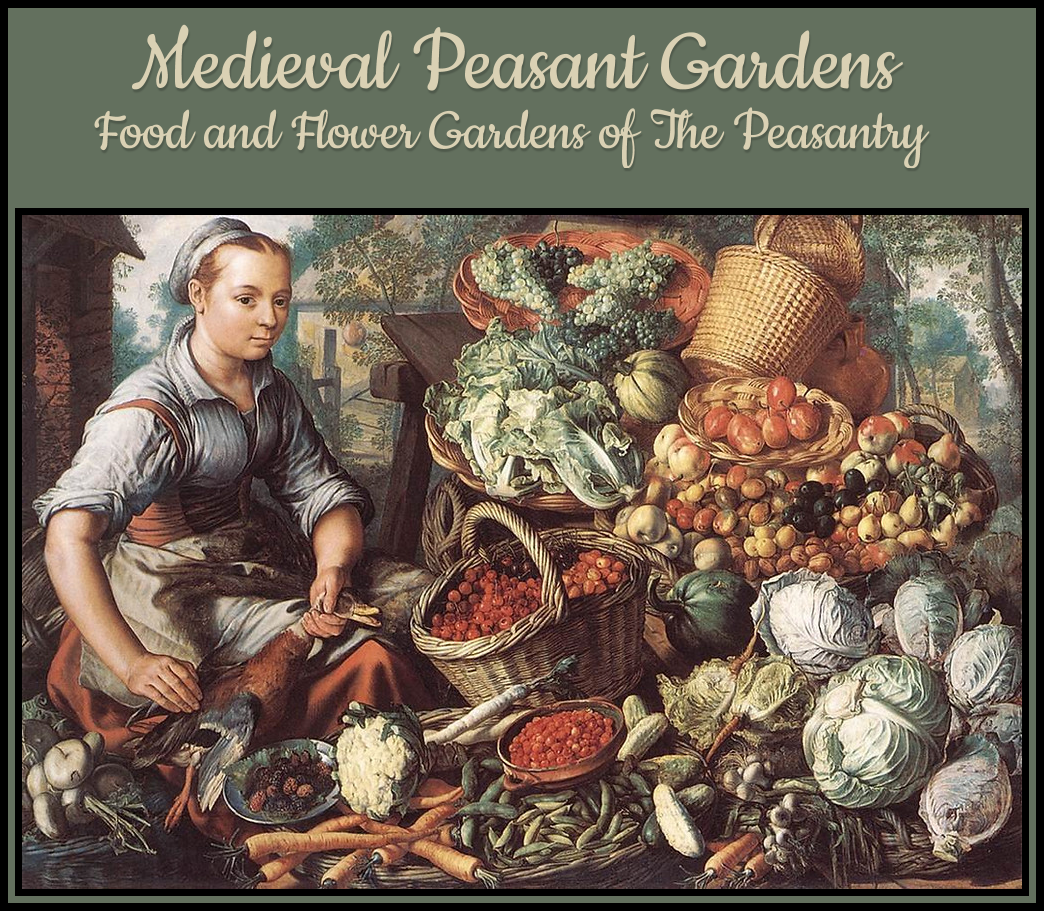

The

Peasant's Diet is actually considered a very healthy diet. Eating meat

was a rarity, fish,

poultry, vegetables, grains, dried berries and fruits comprised the

majority of their food intake.

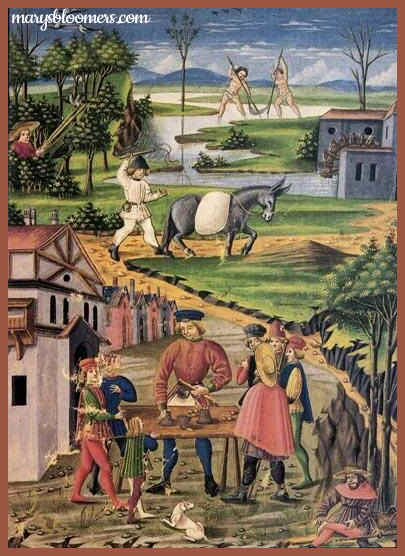

Below

is some 16th century artwork depicting peasant diets and their kitchens.

- Since they carried out heavy work

and were subjected to severe weather conditions during the winter

period, medieval peasants needed to consume many calories a day.

- Cereals were the most widely-used

food, especially for making bread, which was generally made with

wheat flour (however, most peasants made bread with rye flour).

- Wheat and other cereal flour,

such as barley, millet and oats, was also used in the preparation of

soups, ravioli (stuffed with meat) and, rarely, sweet and savoury

pies.

- Although of poor quality, wine

was always present on the tables of peasants.

- It was rare for peasants to eat

meat, since it was often only obtained through hunting, and hunting

was reserved for the noble classes.

- An alternative source of protein

to meat was eggs and fish (especially in mountainous areas rich in

streams).

- Milk was used primarily for the

preparation of cheese and butter: only occasionally was it used as a

drink.

- Butter was a very rare product

for peasants and was found mainly in the diets of the nobility,

unless peasants owned livestock.

- Fresh fruit was not popular due

to storage difficulties, but food such as walnuts, chestnuts and

hazelnuts was easily found in the woods and was easy to preserve for

a long time.

- Although cereals represented the

basis of every meal, vegetables such as cabbage, beets, onions,

garlic and carrots were also very common foods, and were grown in

peasant gardens..

- Many of these vegetables were

consumed on a daily basis by farmers and manual workers and,

therefore, were considered less prestigious foods than meat. Nobles

and richfolk avoided these foods.

Foraging

was also important, and mushrooms, herbs, and other root vegetables were

commonly used in making "pottage",

a type of stew made in a pot. Pea pottage was the main choice

for supper and would be slow-cooked over a fire. It was a very hearty

and healthy meal, usually containing peas, onions and herbs found in the

wild, or grown in their gardens. Spices were far too expensive and out

of reach for most peasants, so instead, many got creative with the herbs

they could grow or find.

Among

the useful garden flowers were those of the artemisia family.

Southernwood’s hair-like leaves were used to relieve fevers and wounds

and, when dried, it was valued for its aroma. The ability to purge a

person of worms and poisons was attributed to wormwood, which was also

respected as a cure for constipation and stomach discomfort, and as a

flea repellent (as was pennyroyal).

Wormwood has a bitter taste, unlike mugwort, which was used to flavor

drinks.

The tansy flower was an insect repellent. The entire plant is aromatic

and bitter to the taste, and all parts of the plant were used in

cooking.

Another useful flower was the marigold, which was used both as a

medicine, against stings and pestilence, and in cooking, as a bitter

spice. Marigolds were well-known insect repellents in the garden.

The blue iris had many uses. The iris root made a good ink and, when

dried, had a sweet smell. Iris leaves could be used in making mats,

patching thatched roofs, or for rushes used in covering floors. The iris

also made a dark blue juice that was used for spot removing, as a salve

for teeth and gums, and as an ingredient in a dye for cloth.

Periwinkle

garlands and wreaths could easily be woven because of the long, supple

stems, and the plant grew low, making it a useful and attractive ground

cover. Medieval English liked flowery meadows, or meads, of

scythe-mown grass, fragrant herbs, and flowers like violets, daisies,

primroses, and periwinkles, to walk, dance, and lie among the visual

beauty and surrounding aromas. Violets were popular, and symbolic of

humility, freshness, purity, and innocence. Dishes made were sometimes

garnished with violets. The petals were used as an emetic and purgative,

and the oil could scent a bath or soothe the skin. Like periwinkles,

daisies were made into garlands and crowns, and were included in

gardens.

The primrose could be made into wine. The leaves were used on wounds to

ease pain and on the skin to avoid blemishes, and they were eaten to

ease muscle aches. The petals were also eaten for pain relief, cooked

into tansy cakes and pottages, and floated in comforting baths.

The

gillyflower, ancestor of the carnation, was respected for its usefulness

and attractiveness. It was used in cooking as a spice for its aroma and

clove-like taste, and was used to cover the bitter taste of some

medicines as well as in wine and ale.

The seeds of the peony were used in flavoring meat, or were eaten raw to

warm the taste-buds and stabilize the temperament. They were also drunk

in hot wine and ale before retiring at night to avoid disturbing

dreams.

Sweet woodruff was frequently used for garlands, with a sweet fragrance

and white color, and was also added to drinks. The leaves were so

scented that they were known as “sweetgrass,” and were strewn when

dried on floors and packed with clothes as a freshener.

The

white rose was a garden favorite.

Red roses were also found in

England

throughout the Medieval period. Roses were

used as symbols of the Holy Spirit, and were scattered in churches.

Along with these cultivated roses there was the native wild rose, known

as the sweet briar or eglantine. It has a lovely fragrance, is a good

climber for walls and fences, and was used in the making of mead and

various medicines. The flowers of Medieval cultivated roses were

smaller, more open, and more fragile than today's roses, and they had a

more delicate fragrance. The Medieval rose plants were more like

rambling bushes, and the thorns were longer and more plentiful. When the

rose petals were dried and powdered they had the most powerful

fragrance. The petals of the red rose were used in the making of rose

water, rose oil, rose preserves, garnishes, and rose sugar.

The

lily was a special devotional flower, associated with the Virgin

Mary.

The white petals represented her purity, and the golden anthers the

light of her soul. The lily was an ancient fertility symbol. The lily

represented purity, innocent beauty, and chastity, a parallel for the

virgin birth of Christ. The central setting of The Song of Songs

in the Old Testament is that of a garden. Therefore the example of

sensual literature most widely known to Medieval people took place in a

garden.

Traditional Medieval Pottage Stew

This sounds like something i would make in a crockpot as

a slow-cooked stew or soup for cold winter days.

| "Pottage" Stew, from Old French pottage 'food

cooked in a pot') is a term for a thick soup or stew made by

boiling vegetables, grains, and, if available, meat or fish. It

was a staple food for many centuries. Pottage consistently

remained a staple of the poor's diet throughout most of 9th to

17th-century Europe. It was meant to keep a peasant or serf

working and healthy.

Pottage was typically slow-boiled for several

hours until the entire mixture took on a homogeneous texture and

flavor; this was intended to break down complex starches and to

ensure the food was safe for consumption. It was usually served

with bread, when available.

Pottage ordinarily consisted of various

ingredients, mostly, if not all, vegetables that were easily

available to serfs and peasants, and could be kept over the fire

for a period of days, during which time some of it could be

eaten, and then more ingredients added. The result was a dish

that was constantly changing in flavor. Today, we would consider

Pottage to be a healthy part of our fast-food-addicted diets.

Very little meat or fats appeared on a peasant's plate.

The earliest known cookery manuscript in the

English language, written by the court chefs of King Richard II

in 1390, contains several pottage recipes including one made

from cabbage, ham, onions and leeks. During the Tudor period, a

good many English peasants' diets consisted almost solely of pottage.

Some peasants ate self-cultivated vegetables like cabbages and

carrots and a few were able to supplement this from fruit

gardens with fruit trees nearby.

Some pottages that were typical of medieval

cuisine were jelly (animal flesh or fish in aspic),

mawmenny (a thickened stew of capon or similar fowl), and pears

in syrup. There were also many kinds of pottages made of

thickened liquids (such as milk and almond milk) with mashed

flowers or mashed or strained fruit.

Typical Pottage Recipe -Add game meats,

poultry, bits of pork, beef or fish, when available. The

main components were vegetables like peas, carrots, potatoes,

cabbage, spinach, turnips, parsnips and rutabagas, and a variety

of grains in a milk or broth “stew”. Meat, cheeses or eggs

could be added. Herbs were used to give flavor. Pottage was a

healthy and hearty recipe that filled you up, kept you

warm and your energy levels high.

Suggested

Ingredients:

1

¾ c. chopped vegetables of your choice. Include root

vegetables.

“knob” of butter (2-3 tablespoons)

¼ c. uncooked oats

Fresh, chopped

garden herbs and seasonings of any type

Onion, shallots or scallions

1 pint of vegetable broth or stock

Variation:

include small, cubed bits of game, ham, beef, chicken or fish

Method:

1.

Melt butter in a cauldron or dutch oven, and fry the vegetables

to soften them.

2.

Add the chopped herbs and oats and stir gently.

3.

Carefully pour in the stock. Cover with a lid and simmer slowly,

stirring from time to time, for several hours.

4.

Once the oats have thickened the sauce, and the vegetables are

softened, the pottage is ready.

To

serve enough for a family, double or triple the amount of

ingredients. Serve with hot, crusty bread, and use the bread to

sop up the juices.

To

use the traditional long-cooking method over a period of days -

serve some of the pottage when ready, and add more ingredients

to the pot. Simmer again with more broth and oats if needed,

rotating the added ingredients as the stew is eaten. Keep the

pottage consistently hot until the last serving. |

Article ©2021 marysbloomers.com

Compilation and adaptation

Article Compiled using these Sources

The Great Courses Daily

Wikipedia

Wikimedia Commons

Artwork in the Public Domain

Original Manuscripts from The Book of Hours

Chicago Tribune 1987

Historic Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts

Medieval Recipes

Roots Web - Society in King Egbert's Time

The

Medieval Castle Gardens-->

Monastery

and Cloister Gardens-->

English Cottage Flower Garden--->

To

learn about American Slave Gardens, click

here.

Design, graphics,

articles and

photos ©2008-2021 marysbloomers.com™

All rights reserved.

|