|

|

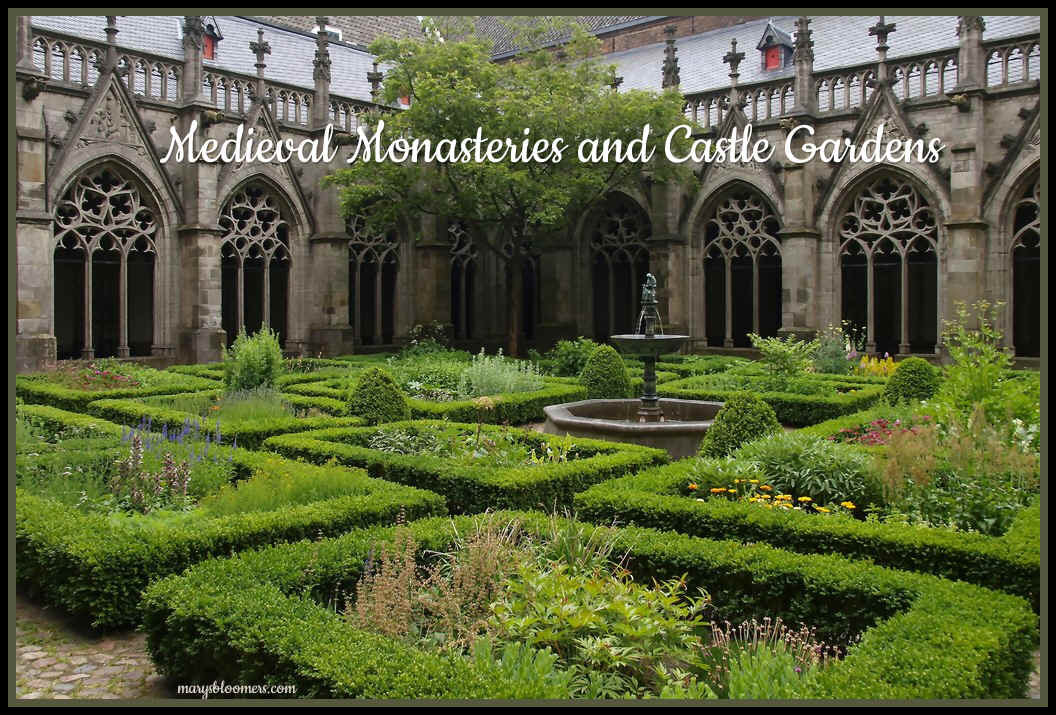

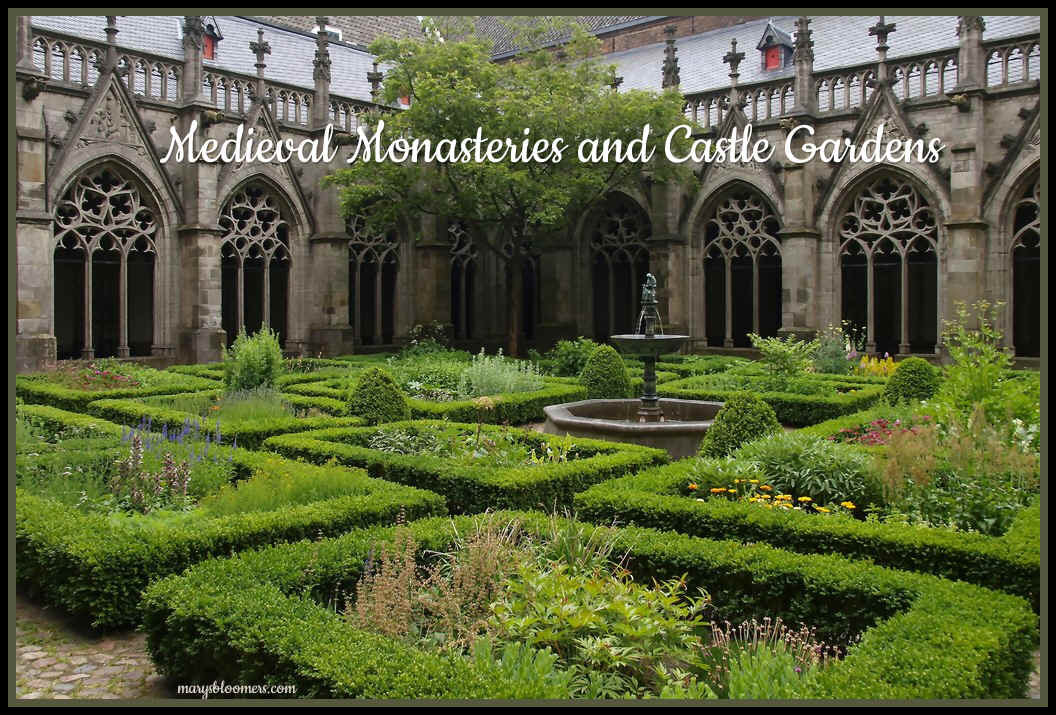

Monastery Gardens

and Cloisters |

|

A monastic garden was used by

many, and for multiple purposes. Gardening was especially important in

the monasteries for supplying their livelihood.

Gardens were mainly in monasteries and manors, but were also developed

by peasants. These were used as kitchen gardens, medicine and herbal

gardens, and even orchards and cemetery gardens. Each type of garden had

its own purpose and meaning, including satisfying medicinal, food, and

spiritual needs. Gardening was important for medicinal use. Monks

used these medicinal herbs on themselves and on the local community. |

|

|

|

Saint Augustine assembled his

company about him: “I assembled, in a garden that Valerius had given me, certain

brethren of like intentions with my own, who possessed nothing, even as I

possessed nothing, and who followed after me.”

Augustine built his

church (with its cloister site corresponding to museum, exedra, and portico

in the old philosopher’s garden); and from the account given, it is obvious

that in this particular instance the habit of meeting and living together in

a garden preceded the foundation of church and monastery.

The buildings of a

medieval monastery were grouped round a peristyle

quite as invariably in the West, where the monks had the strict discipline

of a life in common, as in the East, where they were allowed more personal

freedom; for even the isolated cells in an Oriental cloister were mostly

grouped round a central court.

St Benedict, the founder of the Benedictine monastic order, inspired the cloister life of the sixth century in Western

Europe. He at once ordered that “ all the necessaries “ for the

support of monks should be supplied within the walls, and among these

“necessaries”, water and gardens stood in the first rank: of course

these gardens were for herbs and vegetables. The Benedictines, whose rule

enjoined work in the garden, were the men who handed down the practice of

horticulture right through the Middle Ages. Those Orders, which were not influenced by the Benedictine Rule, and

forbade the monks to do farm work, still seem to have thought a garden

indispensable.

|

|

The Spaniard Isidorus, in his Rule, makes a special point of

having a garden within the cloister, attached to the wall and entered by

the back door, so that the monks should be able to work there and not have

occasion to go outside.

There was a certain tradition in the old Roman

provinces about the cultivation of the choicer kinds of fruit. It is well worth noting that

in Norway, even to this day, none but the finest and choicest fruit trees

are found on the site of an old monastery.

The Plan of Saint Gall is a

medieval architectural drawing of a monastic compound dating from

820–830 AD. It depicts an entire Benedictine monastic compound,

including churches, houses, stables, kitchens, workshops, brewery,

infirmary, and a special house for bloodletting. According to

calculations based on the manuscript's tituli the complex was meant to

house about 110 monks, 115 lay visitors, and 150 craftmen and

agricultural workers. The Plan was never actually built. The planned

church was intended to keep the relics of Saint Gall.

The Plan of Saint

Gall

Buildings of the Abbey

of Saint Gall, according to the historical plan from the early 9th century

- Was apparently never built

The Plan depicts 40

ground plans which include not only the properly monastic buildings

(basilica, cloister, abbot's house and cemetery), but also secular

buildings for the use of lay workers and visitors.

-

Sacred: basilica,

round towers, hostel for visiting monks, abbot's house, cemetery and

cloister complex.

-

Lay: elite guest

houses, servant quarters, hospice for pilgrims and the poor.

-

Educational:

novitiate and outer school for the elite.

-

Medicinal:

infirmary, physician's house, bloodletting house, herb garden.

-

Agricultural and

artisanal: workshops, animal pens, houses for agrarian workers and

gardens.

|

|

The St. Gall

Plan represents a Benedictine monastery, the Benedictine Rule being

applied in the architectural design.

One of the main aspects of the Rule

was the ascetic life of the monks who had to dedicate themselves to

prayer, meditation and study, and not worry about worldly matters.

For this purpose, the Benedictine

Rule required a monastery which was self-sufficient, and that which

provided for the monks all the necessary facilities, food, and water.

The

monk's cloister

The monastic cloister occupies the

centre of the Plan. It is placed in the southeast aligning itself both

with the sacred east and with the poor – the accommodation for

pilgrims and the poor is placed in the east just beneath the cloister

– far from the worldly commodities and pleasures of the secular elite.

The structure of the cloister is

highly symbolic.

It is a closed space looking inwards to its own center, where a savin

tree is placed – sauina

– illustrating the ideal of a monk's experience removed from the

world.

It is four-square, and four paths

lead from its covered galleries to the center – symbolizing

Jerusalem and its four rivers.

The cloister is surrounded by

two-storied buildings consisting of the warming room and dormitory to

the east, the refectory, vestiary and kitchen to the south, and the

cellar and larder to the west.

The monks, as well as the abbot, had

a private entrance to the basilica either through their dormitory or

through the portico of the cloister. |

|

A general garden was

needed for food supply. Some vegetables could also be used for medicinal

purposes, such as garlic.

Monks had a mainly vegetarian diet. Vegetables high in starch or in flavor

were sought after for the gardens.

Cottage gardens were widely used to

grow vegetables, and typically looked wild. However, patches in the

cottage garden were found to be grouped by vegetable family, such as the Allium

family, consisting of the leek (Allium porrum), onion (Allium

cepa), and garlic (Allium sativum).

|

Plants

found in the hortis at St. Gall

|

|

Scientific

name

Common name

|

Vegetable

name found in the Plan of St. Gall

|

Scientific

name

Common name

|

Vegetable

name found in the Plan of St. Gall

|

|

Allium

sativum

Garlic

|

Aleas

|

Coriandrum

sativum

Coriander

|

Coliandrum

|

|

Anethum

graveolens

Dill

|

Anetum

|

Lactuca

spp.

Lettuce

|

Lactuca

|

|

Allium

ascalonicum

Shallot

|

Ascalonicas

|

Nigella

sativa

Black

cumin,

Love-in-a-Mist

|

Git

|

|

Allium

cepa

Onion

|

Cepas

|

Papaver

somniferum

Poppy

|

Papaver

|

|

Allium

porrum

Leek

|

P[o]rros

|

Papaver

sp.

Poppies

|

Magones

|

|

Allium

sativum

Garlic

|

Aleas

|

Pastinaca

sativa

Parsnip

|

Pestinachas

|

|

Anthriscus

cerefolium

Chervil

|

Cerefolium

|

Petroselinum

crispum

Parsley

|

Petrosilium

|

|

Apium

graveolens

Celery

|

Apium

|

Raphanus

sativus

Radish

|

Radiches

|

|

Beta

vulgaris subsp. cicla

Chard

|

Betas

|

Satureia

hortensis

Summer

savory

|

Sataregia

|

|

Brassica

Cabbage

|

Caulas

|

|

|

|

The

physic garden or herbularis

|

|

Plants

found in the physic garden at St. Gall

|

|

Scientific

name

Common name

|

Plant

name found in the Plan of St. Gall

|

Scientific

name

Common name

|

Plant

name found in the Plan of St. Gall

|

|

Balsamita

vulgarita

Costmary

|

Costo

|

Mentha

pullegium

Pennyroyal

|

Pulegium

|

|

Cuminum

cyminum

Cumin

|

Cumino

|

Nasturtium officinale

Watercress

|

Sisimbria

|

|

Trigonella

foenum-graecum

Greek hay

|

Fenegreca

|

Rosa

spp.

|

Rosas

|

|

Foeniculum

vulgare

Fennel

|

Fenuclum

|

Rosmarinum

officinalis

Rosemary

|

Rosmarino

|

|

Iris

germanica

Iris Purple flag

|

Gladiola

|

Ruta

graveolens

Rue

|

Ruta

|

|

Lilium

spp.

Lily

|

Lilium

|

Salvia

officinalis

Sage

|

Saluia

|

|

Levisticum

officinale

Lovage

|

Lubestico

|

Satureia

hortensis

Summer savory

|

Sata

regia

|

|

Mentha

spp.

Mint

|

Menta

|

Vigna

unguiculata

Black eyed pea

|

Fasiolo

|

|

Orchards and Cemetery Gardens

Orchards and cemetery

gardens were also tended to in medieval monasteries. Cemetery gardens,

which tended to be very similar to generic orchards, also acted as a

symbol of Heaven and Paradise, and thus provided spiritual meaning.

The vegetation would provide fruit, such as apples or pears, as well

as manual labor for the monks as was required by the Rule of Saint

Benedict.

According to Saint Benedict, idleness is the enemy of the soul, and

for a monk, daily life was meant to be spent learning about the Lord

and fighting that spiritual battle for the soul. So, monks used manual

labor and spiritual reading to keep busy and avoid being idle.

Monks of this time typically would

use astronomy and the stars to determine religious holidays for every

year. They also used astronomy to help in figuring the best time of

year to plant their gardens as well as the best time to harvest.

These gardens were enclosed with fences, walls or hedges in order to

protect them. Stone and brick walls were typically used by the

wealthy, in manors and monasteries. Wattle fences were used by all

classes, and were the most common type of fence. They were made using

local saplings and woven together. They were easily accessible and

durable, and could even be used to make beds. Bushes were also used as

fencing, as they provided both food and protection to the garden.

Gardens were typically arranged to allow for visitors, and were

constructed with pathways for easy access. It was not uncommon for the

gardens to outgrow the monastery walls, and many times the gardens

extended outside of the monastery and would eventually include

vineyards as well.

|

Trees

found in the orchard at St. Gall

|

|

Scientific

name

Common

name

|

Tree

name found in the Plan of St Gall

|

Scientific

name

Common

name

|

Tree

name found in the Plan of St Gall

|

|

Castanea

sativa

Chestnut

|

Castenarius

|

Pyrus

spp.

Pear

|

Perarius

|

|

Corylus

avellana

Hazel

|

Auellanarius

|

Prunus

domestica

Plum

|

Prunarius

|

|

Cydonia

oblonga

Quince

|

Guduniarius

|

Prunus

dulcis

Almond

|

Amendalarius

|

|

Ficus

carica

Fig

|

Ficus

|

Prunus

persica

Peach

|

Persicus

|

|

Malus

spp.

Apple

|

M[alus]

|

Sorbus

domestica

Service tree

|

Sorbarius

|

|

Mespilus

germanica

Medlar

|

Mispolarius

|

|

|

|

Morus

nigra

Black

mulberry

|

Murarius

|

|

|

|

| An irrigation and

water source was imperative to keeping the garden alive. The most

complicated irrigation system used canals. This required that the

water source be placed at the highest part of the garden so gravity

could aid in the distribution of the water. This was more commonly

used with raised bed gardens, as the channels could run in the

pathways next to the beds.

Kitchen garden ponds also were

used in the 14th and 15th centuries, and were meant to offer

ornamental value. Manure was placed in the ponds to provide

fertilization and water was taken straight from the pond to water the

plants.

The tools that were used at the

time were similar to those gardeners use today. For instance, shears,

rakes, hoes, spades, baskets, and wheel barrows were used and are

still important today.

There was even a tool that acted

much like a watering can, called a thumb pot. Made from clay, the

thumb pot has small holes at the bottom and a thumb hole at the top.

The pot was submerged in water, and the thumb hole covered until the

water was needed. A perforated pot was also used to hang over plants

for constant moisture.

Castle Gardens In The

Middle Ages

It was not only in the great monasteries that people cared for roses and

other flowers. Even a hundred years later, much of the joy in feast and garden

appears in the poems of Fortunatus. The French kings worked to lay out

lovely gardens. Ultrogote, wife of Childeric I, was famous for the rose garden

she had planted by her palace.

In the days of the next centuries, the nobles had to

relinquish many of their gentler manners and customs. They were compelled by the

unrest and insecurity of those days to strengthen their places, and contract

them into a smaller compass. Nothing remained of the fine buildings of Bishop

Sidonius’ time except the defensive parts of the walls and the towers of the

keep, the stronghold with its dependent farm-buildings about the inner court.

The noble owners were obliged to build their castles on almost inaccessible

mountain-tops, where there was very little space, or down in the plain, with

wide moats; and in neither case was there room to have a garden. Moreover there

was not much inclination for peaceful cultivation of the ground, and the men

brought in from the chase everything that was wanted in the kitchen.

But the garden was not entirely absent from the

old castles.

The ladies were the gardeners, for they had been taught by monks how to plant

healing herbs among their vegetables, so that they not only got extra dishes and

green food for the table, but were also able to help the sick and wounded in

castle or village. In the season of flowers, they enjoyed the beauty of many

colours, and the young people used to weave garlands for themselves

and their companions.

|

|

|

|

The garden was put near the windows of the women’s

quarters, so as to be under the eye of the lady of the castle. It was good to

see the garden from above, for it lay like a many-coloured carpet, small and

delightful to behold.

It was not often possible to walk straight out from the

women’s rooms into the garden, which was generally set apart and enclosed, and

they went out of the house by a “very narrow” door.

Often, the garden was close to the mansion, with a staircase leading down to

it, as in the garden is where the lady would desire to stroll. That's where

you'll find the

charming garden of lilies and a fountain.

|

The Garden

of Trees

|

The "garden of trees" was the Medieval garden's pleasure-ground.

Fruit-bearing trees came first,

but it was not only fruit trees that were planted, but a medley of trees

desired for their shade and their beauty.

A Latin fable describes a noble garden

in which an oak grew among flowers and herbs, it gave its shade to the sick king, and a pure clear stream flowed

through the garden.

In Parsifal there are found in the Schlossberg garden, together with

the fairest flowers, fig trees, pomegranates, olives, and vines.

It is not confined to the tree garden, but is also the glory of the castle court with a lawn and a

fountain.

It is the proper tree for social life and parties, and it also stands

out in the pasture lands.

In time, branches are extended widely, supported on

pillars, with a seat below; often there are benches actually in the boughs;

sometimes the whole tree is surrounded by a barrier. |

|

|

|

In the garden itself, people liked best to sit on the smooth turf seats, which

mostly ran along the walls and were either propped up with bricks or stood alone.

In the same way they sat about at games or in conversation, or for weaving

wreaths. They sat on the grass, for here the flowers were not set out in beds,

but grew scattered about anywhere on the grass.

In the middle of the flowery part is the fountain, which keeps the lawn from

getting dry and bare.

The paths between the beds were hard and sanded, very nicely and evenly kept.

When indeed the garden was to be particularly ornamental, the flower beds had tiles

round them.

Often. these trees were set in the middle of

flower beds.

This favorite form was used for the tree at the Festival of

Spring on May Day, and artificial fruits were hung on the crowns as an

attraction to the dancers.

|

|

The Arbor

The arbor was of very great importance in the gardens of the Middle

Ages.

It was known to the ancients in the form of a pergola or trellis-work,

covered with green, possibly supported on posts, and very attractive, but in

gardens of that early date not so necessary; for the portico gave a convenient

shelter against sun or bad weather in the larger gardens, and in the smaller

ones at private houses, there were generally buildings all a round.

But now, the

garden was mostly a thing set apart, and needed a real shelter in the open:

roses and honeysuckle covered every sort of arbor.

|

|

|

The walk leading to these bowers could be used to stroll

about in. A rose tree was often grown “so broad and thick that it

can give its shade to twelve knights together; wound around evenly and bent into

a hoop, yet taller than a man; under the same thorny bush there is golden

mullein and lovely grass."

The Labrynth

Another feature appears very early in the gardens of the period, and this,

too, was meant for retreat or for domestic enjoyment—the maze or

labyrinth. When this first found its way into gardens is uncertain. The name

carries us back to the palace of Minos at Crete: the story goes, that no one

could find the way out of its numerous rooms without a guide, and in common

speech the Greeks used the word in that sense.

The symbol for it was a figure

like a circle or a hexagon, within which were a great many lines crossing each

other, and arriving at a point in the middle from which they led out again to

the circumference.

In the early Middle Ages, the Christian churches adopted the same figure as

a symbol, and it was marked in stone on the floor of a church and used by

penitents. History is not sure as to the date when these mazes appeared

in gardens. In one kind, there were paths between hedges taller than a man, so

that anyone wandering about and taking a wrong turn could not see over and set

himself right.

We first hear of a labyrinth in England in connection with Henry

II, who

is said to have hidden the Fair Rosamond, his beloved, in the woodland retreat

at Woodstock; but the earliest authorities of the fourteenth century only

speak of a "House of Daedalus,” where he kept her hidden away. But at

this time, the garden labyrinth cannot have been unknown. Later on, no large garden was

complete without its labyrinth, and in the design of any grounds plan, the

pattern of the pre-Christian maze was preserved.

|

|

|

Medieval Forest Gardens

At an early date, very large

forest gardens were laid out.

This garden was often a park for animals as well: “ Beneath the

marble tower lies a wonderful garden of trees, with walls all round,

and generally with wild animals.”

“The king took two acres or

even more of woodland by the lake, and threw a wall around it.”

This does not remain mere wild

land: it was divided into three parts for different kinds of

animals, and the king had a well-appointed shooting box built, so

that he could look on at the hunt with the ladies.

|

|

Town Gardens

In medieval towns, it was not only the great nobles who set store by

beautiful gardens...

The burghers began more and more to care about gardens.

Every now and then, there is heard some very early rumor about the praise given to gardens in the city of

Paris by the Emperor Julian when he was on his journey to the North.

The

particular commendation is due to the fact that Parisians used to keep vines

and figs round their houses, and protected them through the winter with

coverings of straw. But this is an exception, for it is not until quite late

that we hear of any horticulture in the Northern towns.

At first, gardens were just vegetable plots in front of the town walls,

and the produce was sold in the horticultural markets.

In 1345 the

private gardeners of the great nobles and gentlemen of London had a quarrel

with the alderman, because the noise of the market at St. Paul’s

Churchyard annoyed the inhabitants and passers-by. Naturally there arose at

an early date a trade guild of gardeners.

A Roman document is known about a Gardeners’ Company, and at that time, the Northern towns were not

much behind Italy.

Fruit orchards and vineyards were carefully laid out and

kept up, and any injury done to them was severely punished.

|

|

The towns developed very slowly from want lack of space; and it was only

when they were attached to the larger houses that one found more important

gardens, taken from the space for building

Sometimes medieval town

dwellers were able to have small gardens in the streets alongside the wall,

or at the side of houses which faced towards the river, as so often in Paris

with the more important houses. They had more freedom in the suburbs.

The gardens of village

houses in the Middle Ages naturally developed in a finer way and at an

earlier date than those in towns. In the songs of wandering minstrels we

often hear of the peasant’s garden.

There was generally a plot of ground in front of the house, serving

hospitable ends. Peasants met there as in an arbor to drink together, and

the plot at the back was used for kitchen stuff.

|

|

|

Vintage

Garden Graphics--->

Content, graphics and design ©2020 marysbloomers.com/eyecandee.com

All rights reserved

This

site uses Watermarkly Software

|