|

|

||||||||

|

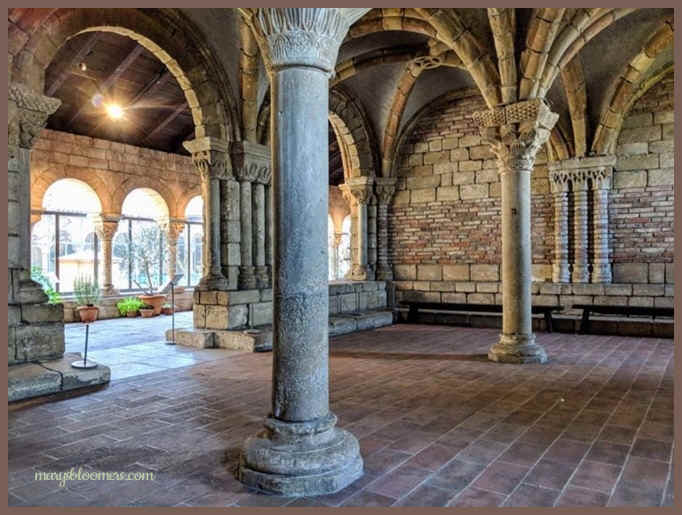

The Cloisters is a branch of New York's Metropolitan Museum, and the only American museum dedicated to the art of the Middle Ages. The renowned Cloisters sits at the northernmost part of the island of Manhattan. Overlooking the Hudson River at Fort Tryon Park, it’s a place out of time: The view across the river was protected when John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated the Palisades on the opposite bank to the state of New Jersey.

In winter, the arcades are glassed in, and the interior walkway becomes a conservatory filled with tender plants such as date palm, orange, rosemary, and bay. Potted bulbs, forced into early bloom, are also on display in late winter and early spring. Cloister gardens are often not linked to their surrounding building - usually accessed by a side door. Though quite different, another walled garden style is the Persian

garden.

|

||||||||

The raised beds of the Bonnefont Cloister Herb Garden hold one of the most specialized plant collections in the world. The foundation of the plant list is a ninth-century edict of the emperor Charlemagne, naming 89 species to be grown on his estates. This list has been supplemented by herbals and monastic records, as well as archaeological evidence. The collection is based on the more than 400 species of plants known and used in the Middle Ages. Plants are grouped and labeled according to their medieval use, whether in cooking, medicine, art, industry, housekeeping, or magic. Most plants had multiple uses, and virtually all plants were believed to have medicinal value. Many herbs, trees, and flowers were used symbolically as well as practically.

Although the plan of the herb garden is typical of a medieval monastic garden, no attempt has been made to replicate that of a particular monastery. The raised beds, wattle fences, and wellhead are all features frequently depicted in medieval sources. Four quince trees grow in the beds at the center of the garden. Tender plants are grown in terracotta pots that can be moved inside in winter, a common gardening practice in northern Europe throughout the late Middle Ages. The Trie Cloister Garden evokes the idealized gardens and landscapes of the Middle Ages. The joy the medieval world felt upon the return of spring was expressed in their verdant, millefleur tapestries, allegorical poems, and paintings. The garden's plantings are inspired by that cherished medieval setting, the enameled mead or flowering meadow.

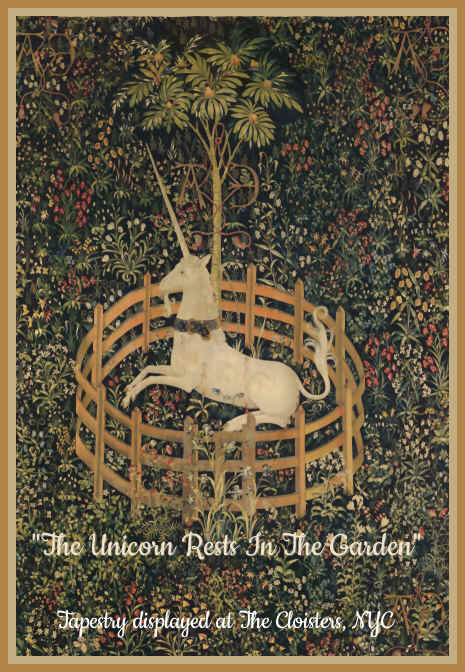

While medieval apothecary and vegetable gardens were orderly, with pleasing symmetry and balance, the medieval fantasy garden was a place of unbridled and untamed nature. This ecstatic vision of nature is evident in the Unicorn Tapestries' myriad of flowers and fruits. Regardless of their natural cycles: fall fruits, winter berries, and spring flowers coexist in a vision of an eternal spring. Much of the flora found blooming in the tapestries is cultivated here, though the plants bloom in their proper seasons. From the south wall of Bonnefont Garden, is an orchard of lady apples and other medieval fruits such as medlar, quince, currants, and elderberries. Orchards were associated with monasteries, manor houses, and parks, and were often enclosed to keep out thieves. A willow hedge separates the orchard precinct from the Museum lawn and the park beyond it. The ground under the fruit trees is planted to evoke the flowering meadow that was a common feature of medieval pleasure grounds. The Cloisters' orchard meadow is stocked with spring bulbs that naturalize and form large colonies over time. A variety of herbs and flowers reseed themselves each year, and are cut back to the ground in late summer.

A prominent feature of these formal gardens is a geometric layout following geometric and visual principles, implemented to nature by water channels and basins which divide the enclosed space into clearly defined quarters, a principle that has become known as Chahar Bagh (four gardens), waterworks with channels, basins, fountains and cascades, pavilions, prominent central axes with a vista, and a plantation with a variety of carefully chosen trees, herbs. and flowers. The old-Iranian word for such gardens "pari-daizi' expresses the notion of an earthly paradise that is inherent to them. As such, they are a metaphor for the divine order and the unification and protection of the ones who do good. Their counterparts on earth fulfill a similar function. These principles are brought to perfection in the gardens of the emperor as the "good gardener".

The Persian style often attempts to

integrate indoors with outdoors, through the connection of a surrounding

garden with an inner courtyard. Starting from the 12th to 13th century, tombs for members of the royal family or important personalities were placed into such formal gardens, providing believers a chance to benefit from the spirituality of a venerated person and the particular aura of the garden. European garden design began to influence Persia, particularly the designs of France, and out of Russia and the United Kingdom. Western influences led to changes in the use of water and the species used in bedding. Iran's dry heat makes shade important in gardens, which would be nearly unusable without it. Trees and trellises largely feature shade; pavilions and walls are also structurally prominent in blocking the sun. The heat also made water important, both in the design and maintenance of the garden. Irrigation may be required, and may be provided via a form of tunnel called a qanat, that transports water from a local aquifer. Well-like structures then connect to the qanat, enabling the drawing of water. Trees were often planted in a ditch called a juy, which prevented water evaporation and allowed the water quick access to the tree roots.

|

||||||||

Content, graphics,

photos and design ©2020 marysbloomers.com

All rights reserved

This

site uses Watermarkly Software