|

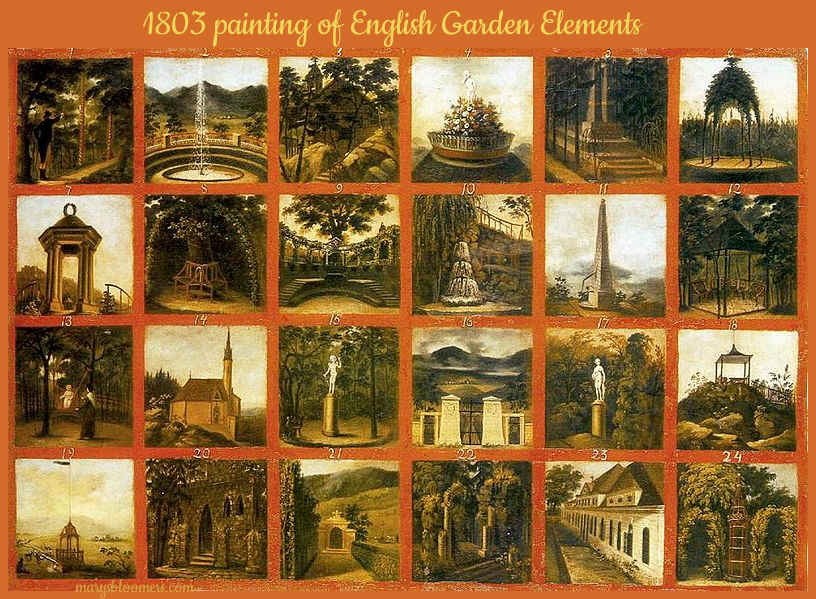

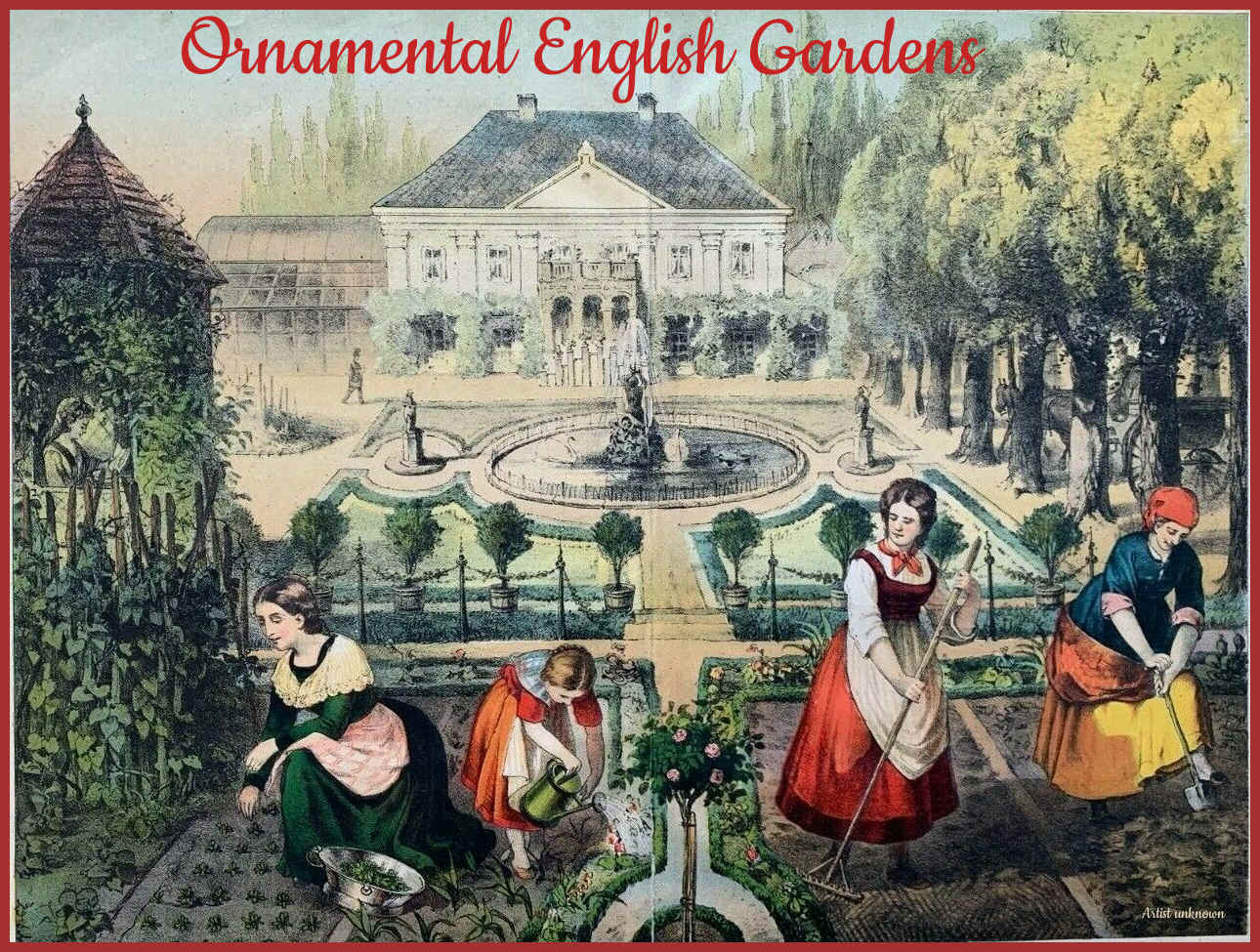

The great age of the English garden Characteristics and History of the 17th and 18th century English garden The large European "English park" contains a number of Romantic elements. Always present is a pond or small lake with a pier or bridge. Overlooking the pond is a round or hexagonal pavilion, often in the shape of a Roman temple. Sometimes the park also has a Chinese pavilion. Other elements include a grotto and imitation ruins. The dominant style was revised in the early 19th century to include more "gardenesque" features, including shrubbery with gravelled walks, tree plantations to satisfy botanical curiosity, and, most notably, the return of flowers, in sweeping planted beds. This is the version of the landscape garden most imitated in Europe in the 19th century. The outer areas of the "home park" of English country houses retain their naturalistic shaping. English gardening since the 1840s has been on a more restricted scale, closer and more tied to the residence. To learn how to create an old-fashioned Cottage Garden, visit

this page.

"English garden" is characteristically on a smaller scale

than the historic grand landscape and English Garden Parks. A second style of English garden, which became popular during the 20th century in France and northern Europe, is the late 19th-century English cottage garden.

History of English Gardens and Landscape Parks The Italian Renaissance garden emerged in the late 15th century at villas in Rome and Florence, inspired by classical ideals of order and beauty, and intended for the pleasure of the view of the garden and the landscape beyond, for contemplation, and for the enjoyment of the sights, sounds and smells of the garden itself. In the late Renaissance, the gardens became larger, grander and more symmetrical, and were filled with fountains, statues, grottoes, water organs and other features designed to delight their owners and amuse and impress visitors. The style was imitated throughout Europe, influencing the gardens of the French Renaissance and the English garden. The Italian pronouncement that “things planted should reflect the shape of things built” had ensured that gardens were essentially open-air buildings and the making of them the province of architects. Before the 18th century, geometric regularity had been applied in great details of design. England was committed to a version of the French geometric extension garden but with an emphasis on English grass lawns and gravel walks. Dutch influence led to widespread use of topiaried yew and box shrubbery. Transition from formal and symmetrical to naturalistic In 18th-century England, people became increasingly aware of the natural world. Rather than imposing their man-made geometric order on the natural world, they began to adjust to it. Literary men, notably Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison, began to question the propriety of trees being carved into artificial shapes as substitutes for masonry and to advocate the restoration of free forms. The English landscape garden, also called English landscape park or simply the English garden is a style of "landscape" garden which emerged in England in the early 18th century, and spread across Europe, replacing the more formal, symmetrical jardin à la française of the 17th century as the principal gardening style of Europe. The English garden presented an idealized view of nature. The man who led the revolt against the “artificial,” symmetrical garden style was the painter and architect William Kent. The informal garden style originated as a revolt against the architectural garden, and drew inspiration from paintings of landscapes. The English garden usually included a lake, sweeps of gently rolling lawns set against groves of trees, and recreations of classical temples, Gothic ruins, bridges, and other picturesque architecture, designed to recreate an idyllic pastoral landscape. The process of relaxing the garden’s architectural discipline advanced with speed. At Stowe, Buckinghamshire, the original enclosed geometrical garden was amended over the years until a totally different, “irregular formality" was achieved. Trees were allowed to assume their natural forms, and a large expanse of water was redesigned into two irregularly shaped lakes. The use of the "ha-ha", or sunken fence, to create, and at the same time conceal the physical division between garden and contiguous park grounds (a division needed to keep grazing animals out of the garden), was a major step in the creation of the new, “natural” garden.

Created and pioneered by William Kent, the “informal” garden style originated as a revolt against the architectural garden and drew inspiration from paintings of landscapes. The English garden usually included a lake, sweeps of gently rolling lawns set against groves of trees, and recreations of classical temples, Gothic ruins, bridges, and other picturesque architecture, designed to recreate an idyllic pastoral landscape. The English landscape garden was usually centred on the English country house. The face of the “country without” was

altered by the rage that afflicted the English nobility for planting

vast areas of trees. Lancelot "Capability" BrownThe most influential figure in the later development of the English landscape garden was Lancelot "Capability" Brown, who began his career in 1740 as a gardener at Stowe. He succeeded William Kent in 1748. Brown's contribution was to simplify the garden by eliminating geometric structures, alleys, and parterres near the house and replacing them with rolling lawns and extensive views out to isolated groups of trees, making the landscape seem even larger. "He sought to create an ideal landscape out of the English countryside."H created artificial lakes and used dams and canals to transform streams or springs into the illusion that a river flowed through the garden. He compared his own role as a garden designer to that of a poet or composer. Brown designed 170 gardens. Although the adherents of the new English school of garden design were in agreement in their abhorrence of the straight, Classical line and the geometrically ordered garden, they did not agree on what the natural garden should be. Unlike Brown, for example, the taste for the romantic and the literary led many to seek inspiration in the dramatic and the bizarre, in the remote past, and in remote, exotic places. Another school of opinion created what might be called the English garden of poetic bric-a-brac. The aim in this garden was to create an air of accidental discovery and surprise, and to arouse varied sensations (solemnity, sublimity, terror) in the viewer—sensations evoked by associations with the remote in time and space. Wandering through the grounds, one came upon Classical statues, urns, and temples; Gothic ruins, ivy-covered and inhabited by owls; or Chinese pagodas and bridges. After Horatio Walpole recorded the first appearance of chinoiserie at Wroxton in 1753, “Chinese” and Gothic details were featured, together with Classical temples, in most fashionable grounds. By 1760 the enthusiasm for this style had diminished in England, but in continental Europe the poetic bric-a-brac garden (le jardin anglo-chinois, or le jardin anglais, as the French called it) was almost as widely emulated as Versailles had been.

sources: Quick Links Content, graphics,

photos and design ©2020 marysbloomers.com |