|

|

||||

A disciplined, nature-based landscaping approach Japanese gardens are traditional gardens with design concepts that are accompanied by Japanese aesthetics and philosophical ideas, avoid artificial ornamentation, and highlight the natural landscape.Plants and worn, aged materials are generally used by Japanese garden designers to suggest an ancient and faraway natural landscape, and to express the fragility of existence as well as time's unstoppable advance. Garden Elements The ability to capture the essence of nature makes the Japanese gardens distinctive and appealing. Japanese gardens have always been conceived as a representation of a natural setting. The Japanese have always had a spiritual connection with their land and the spirits that are one with nature, which explains why they prefer to incorporate natural materials in their gardens. Traditional Japanese gardens can be categorized into three types: tsukiyama (hill gardens), karesansui (dry gardens) and chaniwa gardens (tea gardens). The main purpose of a Japanese garden is to attempt to be a space that captures the natural beauties of nature.

Traditional Japanese gardens are very different in style from "occidental gardens". The contrast between western flower gardens and Japanese gardens is profound. Western gardens are typically optimized for visual appeal, while Japanese gardens are modeled with spiritual and philosophical ideas in mind. The small space given to create these

gardens usually poses a challenge for the gardeners. Due to the absolute

importance of the arrangement of natural rocks and trees, finding the

right material becomes highly selective. The serenity of a Japanese

landscape and the simple but deliberate structures of the Japanese

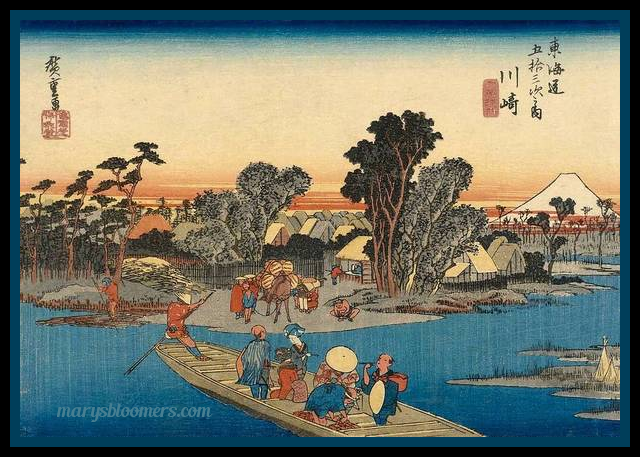

gardens are what truly make the gardens unique. Ancient Japanese art inspired past garden designers. The Japanese garden had its own distinct appearance beginning with the Edo period.The idea of these unique gardens began during the Asuka period (c. 6th to 7th century). Japanese merchants witnessed the gardens that were being built in China and brought many of the Chinese gardening techniques and styles back home. In Heian-period Japanese

gardens, built in the Chinese model, buildings occupied as much or more

space than the garden. Water

Japanese gardens always have water, either a pond or stream, or, in the dry rock garden, represented by white sand. In Buddhist symbolism, water and stone are the yin and yang, two opposites that complement and complete each other. A traditional garden will usually have an irregular-shaped pond or, in larger gardens, two or more ponds connected by a channel or stream, and a cascade, a miniature version of Japan's famous mountain waterfalls.

In traditional gardens, the ponds and

streams are carefully placed according to Buddhist geomancy - the art of

putting things in the place most likely to attract good fortune. The Sakuteiki recommends several possible miniature landscapes using lakes and streams: the "ocean style", which features rocks that appear to have been eroded by waves, a sandy beach, and pine trees; the "broad river style", recreating the course of a large river, winding like a serpent; the "marsh pond" style, a large still pond with aquatic plants; the "mountain torrent style", with many rocks and cascades; and the "rose letters" style, an austere landscape with small, low plants, gentle relief and many scattered flat rocks. Traditional Japanese gardens have small islands in the lakes. In sacred temple gardens, there is usually an island which represents Mount Penglai or Mount Hōrai, the traditional home of the Eight Immortals.

The Sakuteiki describes different kinds of artificial island which can be created in lakes, including the "mountainous island", made up of jagged vertical rocks mixed with pine trees, surrounded by a sandy beach; the "rocky island", composed of "tormented" rocks appearing to have been battered by sea waves, along with small, ancient pine trees with unusual shapes; the "cloud island", made of white sand in the rounded white forms of a cumulus cloud; and the "misty island", a low island of sand, without rocks or trees. A cascade or waterfall is an important

element in Japanese gardens, a miniature version of the waterfalls of

Japanese mountain streams. The Sakuteiki describes seven kinds of

cascades. Rocks and Sand

Rock, sand and gravel are an essential feature of the Japanese garden.

A vertical rock may represent Mount Horai, the legendary home of the

Eight Immortals, or Mount Sumeru of Buddhist teaching, or a carp jumping

from the water. Rough volcanic rocks are

usually used to represent mountains or as stepping stones. In ancient Japan, sand and gravel were used around Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. Later it was used in the Japanese rock garden or Zen Buddhist gardens to represent water or clouds. White sand represented purity, but sand could also be gray, brown or bluish-black. Selection and subsequent placement of rocks was and still is a central concept in creating an aesthetically pleasing garden by the Japanese. Dry Rock Gardens The Japanese rock garden, or

"dry landscape" garden, often called a zen garden, creates a

miniature stylized landscape through carefully composed arrangements of

rocks, water features, moss, pruned trees and bushes, and uses gravel or

sand that is raked to represent ripples in water. Japanese rock gardens became

popular in Japan in the 14th century thanks to the work of a Buddhist

monk, Musō Soseki (1275–1351) who built zen gardens at the five

major monasteries in Kyoto.

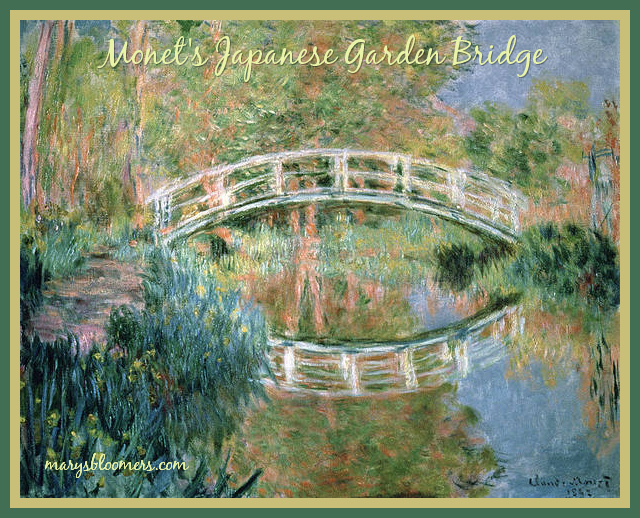

During the Heian period, the concept of placing stones as symbolic representations of islands – whether physically existent or nonexistent – began to take hold, and can be seen in the Japanese word shima, which is of "particular importance ... because the word contained the meaning 'island' Furthermore, the principle of "obeying the request of an object", was, and still is, a guiding principle of Japanese rock design that suggests "the arrangement of rocks be dictated by their innate characteristics". The specific placement of stones in Japanese gardens to symbolically represent islands (and later to include mountains), is found to be an aesthetically pleasing property of traditional Japanese gardens. Stones, which constitute a fundamental part of Japanese gardens, are carefully selected for their weathering and are placed in such a way that they give viewers the sense that they ‘naturally’ belong where they are, and in combinations in which the viewers find them. As such, this form of gardening attempts to emblematically represent (or present) the processes and spaces found in wild nature, away from city and practical concerns of human life. Rock placement is a general "aim to portray nature in its essential characteristics" – the essential goal of all Japanese gardens. While stones are also central to Japanese gardening … as stones were part of an aesthetic design and had to be placed so that their positions appeared natural and their relationships harmonious. The concentration of the interest on such detail as the shape of a rock or the moss on a stone lantern led at times to an overemphatic picturesqueness and accumulation of minor features that, to Western eyes accustomed to a more general survey, may seem cluttered and restless. Such attention to detail can be seen at places such as Midori Falls in Ishikawa Prefecture, as the rocks at the waterfall's base were changed at various times by six different daimyōs. Garden Bridges

The bridge symbolized the path to paradise and immortality. Bridges could be made of stone or of wood, or made of logs with earth on top, covered with moss; they could be either arched or flat. If they were part of a temple garden, they were sometimes painted red, following the Chinese tradition, but for the most part they were unpainted. When large promenade gardens became popular, streams and winding paths were constructed, with a series of bridges, usually in a rustic stone or wood style, to take visitors on a tour of the scenic views of the garden. Stone lanterns and water basins Japanese stone lanterns ("platform lamp") originally were located only at Buddhist temples, where they lined the paths and approaches to the temple According to tradition, they were introduced to the tea garden by the first great tea masters, and in later gardens they were used purely for decoration. In its complete and original

form, like the pagoda, it represents the five elements of Buddhist

cosmology. Stone water basins were

originally placed in gardens for visitors to wash their hands and mouth

before the tea ceremony. Trees and flowers Nothing in a Japanese garden is natural or left to chance; each plant is chosen according to aesthetic principles, either to hide undesirable sights, to serve as a backdrop to certain garden features, or to create a picturesque scene, like a landscape painting or postcard. Trees are carefully chosen and

arranged for their autumn colors. The trees are carefully

trimmed to provide attractive scenes, and to prevent them from blocking

other views of the garden. Their growth is also controlled, in a technique

called niwaki, to give them more picturesque shapes, and to make them look

more ancient. It has been suggested that the characteristic shape of

pruned Japanese garden trees resemble trees found naturally in savannah

landscapes. In the late 16th century, a

new art was developed in the Japanese garden; that of the technique of

trimming bushes into balls or rounded shapes which imitate waves.

According to tradition this art was most frequently practiced on azalea

bushes. Fish The use of fish, particularly

colored carp, or goldfish as a decorative element in gardens was borrowed

from the Chinese garden. Goldfish were

developed in China more than a thousand years ago by selectively breeding

Prussian carp for color mutations. Aesthetics The early Japanese gardens

largely followed the Chinese model, but gradually Japanese gardens

developed their own principles and aesthetics. These were spelled out by a

series of landscape gardening manuals, beginning with "Records of

Garden Making" in the Heian Period. However, they often contain

common elements and used the same techniques. Basic Principles It is said that the heart of the Japanese garden is the principle that a garden is a work of art. "Though inspired by nature, it is an interpretation rather than a copy; it should appear to be natural, but it is not wild." Miniaturization. The Japanese garden is a miniature and idealized view of nature. Rocks can represent mountains, and ponds can represent seas. The garden is sometimes made to appear larger by placing larger rocks and trees in the foreground, and smaller ones in the background. Concealment. The Zen Buddhist garden is meant to be seen all at once, but the promenade garden is meant to be seen one landscape at a time, like a scroll of painted landscapes unrolling. Features are hidden behind hills, trees groves or bamboo, walls or structures, to be discovered when the visitor follows the winding path. Borrowed scenery. Smaller gardens are often designed to incorporate the view of features outside the garden, such as hills, trees or temples, as part of the view. This makes the garden seem larger than it really is. Asymmetry.

Japanese gardens are not laid on straight axes, or with a single feature

dominating the view.

Differences between Japanese and Chinese Gardens Japanese gardens during the Heian period were modeled upon Chinese gardens, but by the Edo period there were distinct differences. Architecture.

Chinese gardens have buildings in the center of the garden, occupying a

large part of the garden space. The buildings are placed next to or over

the central body of water. The garden buildings are very elaborate, with

much architectural decoration. Viewpoint. Chinese gardens are designed to be seen from the inside, from the buildings, galleries and pavilions in the center of the garden. Japanese gardens are designed to be seen from the outside, as in the Japanese rock garden or zen garden; or from a path winding through the garden. Use of rocks.

In a Chinese garden, rocks were selected for their extraordinary shapes or

resemblance to animals or mountains, and used for dramatic effect. They

were often the stars and centerpieces of the garden. Marine landscapes. Chinese gardens were inspired by Chinese inland landscapes, particularly Chinese lakes and mountains, while Japanese gardens often use miniaturized scenery from the Japanese coast. Japanese gardens frequently include white sand or pebble beaches and rocks which seem to have been worn by the waves and tide, which rarely appear in Chinese gardens.

The "lake-spring-boat

excursion garden" was imported from China. The Paradise Garden The Paradise Garden appeared

in the late Heian period, created by nobles belonging to the Amida

Buddhism sect.

The tea garden was created as

a setting for the Japanese tea ceremony. Rustic teahouses were hidden in their own little gardens, and small benches and open pavilions along the garden paths provided places for rest and contemplation. In later garden architecture, walls of houses and teahouses could be opened to provide carefully framed views of the garden. The garden and the house became one. Promenade Gardens Promenade or stroll gardens (landscape gardens in the go-round style) appeared in Japan at the villas of nobles or warlords. These gardens were designed to complement the houses in the new sukiya-zukuri style of architecture, which were modeled after the teahouse. These gardens were meant to be seen by following a path clockwise around the lake from one carefully composed scene to another. These gardens used two techniques to provide interest: borrowed scenery, which took advantage of views of scenery outside the garden such as mountains or temples, incorporating them into the view so the garden looked larger than it really was, and "hide-and-reveal", which used winding paths, fences, bamboo and buildings to hide the scenery so the visitor would not see it until he was at the best view point. Edo period gardens also often feature recreations of famous scenery or scenes inspired by literature; Suizen-ji Jōju-en Garden in Kumamoto has a miniature version of Mount Fuji, and Katsura Villa in Kyoto has a miniature version of the Ama-no-hashidate sandbar in Miyazu Bay, near Kyoto. The Rikugi-en Garden in Tokyo creates small landscapes inspired by eighty-eight famous Japanese poems. Small Urban Garden Small gardens were originally

found in the interior courtyards ("inner garden") of Heian

period palaces, and were designed to give a glimpse of nature and some

privacy to the residents of the rear side of the building. They were as small as about 3.3 square meters.

A hermitage garden is a small garden, usually built by a samurai or government official who wanted to retire from public life and devote himself to study or meditation. It is attached to a rustic house, and approached by a winding path, which suggests it is deep in a forest. It may have a small pond, a

Japanese rock garden, and the other features of traditional gardens, in

miniature, designed to create tranquility and inspiration. An example is the Shisen-dō

garden in Kyoto, built by a bureaucrat and scholar exiled by the shogun in

the 17th century. It is now a Buddhist temple. Cultural Significance of Garden-Making In Japanese culture, garden-making is a high art, equal to the arts of calligraphy and ink painting. Gardens are considered three-dimensional textbooks of Daoism and Zen Buddhism. The lessons are contained in

the arrangements of the rocks, the water and the plants. The Japanese rock gardens were intended to be intellectual puzzles for the monks who lived next to them to study and solve. They followed the same principles as the suiboku-ga, the black-and-white Japanese inks paintings of the same period, which, according to Zen Buddhist principles, tried to achieve the maximum effect using the minimum essential elements. Japanese gardens also follow the principles of perspective of Japanese landscape painting. The empty space between the different "planes" is of great importance, and is filled with water, moss, or sand. The garden designers used various optical tricks to give the garden the illusion of being larger than it really is, by borrowing of scenery ("shakkei"), employing distant views outside the garden, or using miniature trees and bushes to create the illusion that they are far away. |

||||

|

|

||||

| Hakonechloa

macra, is a pretty grass. Mosses are used between rocks and

architectural items and in place of lawn grass.

Quince makes a beautiful addition to

Japanese-style planting scheme.

In spring it produces cup-shaped flowers, followed by gold-colored fruits in

autumn. The fruits can be made into an awesome jam. Quince can also be trained as a bonsai tree. Japanese Painted Fern - spread by rhizomes. Intersperse with groundcover moss. Water features can be used in even the smallest of gardens, adding to the ambience through bubbling sounds and they attract the songbirds when used in birdbaths. Ponds can be planted with waterlilies and Japanese flag irises. For smaller gardens, consider garden water bowls or trickling water features. Article is an adaptation of several

entries |

Japanese

Garden and Landscape Graphics Collection --->

New: Mary's Bloomers Gardening Blog

Content, graphics and design ©2020 marysbloomers.com

All rights reserved

This site uses Watermarkly Software