|

THE SHAKESPEARE

GARDEN PUBLISHED BY

THE CENTURY CO. Excerpts

below: "The note here

was charming intimacy. It was a spot where gentleness and

sweetness reigned, and where, perforce, every flower enjoyed the air it

breathed. It was a Garden of Delight for flowers, birds, and men." It touches upon the

culture and horticulture in Shakespeare's time. Lots of plants are named

that would give your Shakespeare Garden the authenticity from history. The illustrations shown are those from the original book. The plant list is invaluable. Portions of this book are compiled below. |

|

THE SHAKESPEARE GARDEN Realizing the importance of reproducing an accurate representation of the garden of Shakespeare's time, the authorities at Stratford-upon-Avon have recently rearranged "the garden" of Shakespeare's birthplace; and the flowers of each season succeed each other in the proper "knots" and in the true Elizabethan atmosphere. Of recent years it has been a fad among American

garden lovers to set apart a little space for a "Shakespeare

garden," where a few old-fashioned English flowers are planted in

beds of somewhat formal arrangement. These gardens are not, however, by

any means replicas of the simple garden of Shakespeare's time, or of the

stately garden as worked out by the skillful Elizabethans.

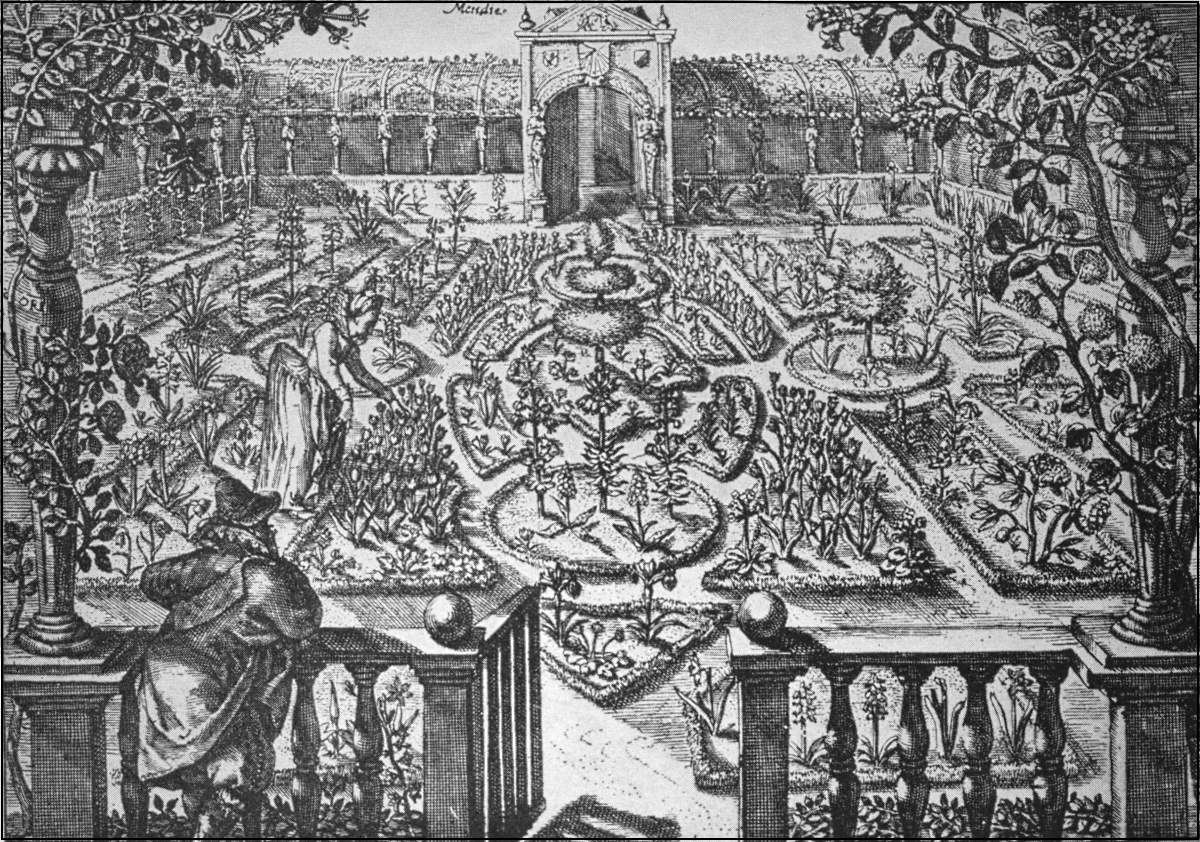

The 4 Principles of The Elizabethan Garden The Elizabethan garden was usually

four-square, bordered all around by hedges and intersected by paths. Stately gardens were usually approached from a terrace running along the line of the house and commanding a view of the garden, to which broad flights of steps led. Thence extended the principal walks, called "forthrights," in straight lines at right angles to the terrace and intersected by other walks parallel with the terrace. The lay-out of the garden, therefore, corresponded with the ground-plan of the mansion. The squares formed naturally by the intersection of the "forthrights" and other walks were filled with curious beds of geometrical patterns that were known as "knots"; mazes, or labyrinths; orchards; or plain grass-plots. Sometimes all of the spaces or squares were devoted to "knots." These ornamental flower-beds were edged with box, thrift, or thyme and were surrounded with tiny walks made of gravel or colored sand, walks arranged around the beds so that the garden lovers might view the flowers at close range and pick them easily. It will be remembered that in "Love's Labour's Lost" Shakespeare speaks of "the curious knotted garden." There are innumerable designs for these "knots" in the old Elizabethan garden-books, representing the simple squares, triangles, and rhomboids as well as the most intricate scrolls, and complicated interlacings of Renaissance design that resemble the motives on carved furniture, designs for textiles and ornamental leather-work (known as strap-work, or cuirs). Yet these many hundreds of designs were not sufficient, for the amateur as well as the professional gardener often invented his own garden "knots." Where the inner paths intersected, a

fountain or a statue or some other ornament was frequently placed. There were four principles that were

observed in all stately Elizabethan gardens. The second principle was to plant the beds with mixed flowers and to let the colors intermingle and blend in such a way as to produce a mosaic of rich, indeterminate color, ever new and ever varying as the flowers of the different seasons succeeded each other. The third principle was to produce a garden of flowers and shrubs for all seasons, even winter, that would tempt the owner to take pleasure and exercise there, where he might find recreation, literally re-creation of mind and body, and become freshened in spirit and renewed in health. The fourth principle was to produce a garden that would give delight to the sense of smell as well as to the sense of vision—an idea no longer sought for by gardeners. Hence it was just as important, and infinitely more subtle, to mingle the perfumes of flowers while growing so that the air would be deliciously scented by a combination of harmonizing odors as to mingle the perfumes of flowers plucked for a nosegay, or Tussie-mussie, as the Elizabethans sometimes quaintly called it. Like all cultivated Elizabethans, Shakespeare appreciated the delicious fragrance of flowers blooming in the garden when the soft breeze is stirring their leaves and petals. There was but one thing to which this subtle perfume might be compared and that was ethereal and mysterious music. |

||||||||

|

The uses of the Elizabethan garden were

many: to walk in, to sit in, to dream in.

Here the courtier, poet, merchant, or country squire found refreshment for his mind and recreation for his body. The garden was also intended to supply flowers for nosegays, house decoration, and the decoration of the church. Sweet-smelling herbs and rushes were strewn upon the floor. One of Queen Elizabeth's Maids of Honor had a fixed salary for keeping fresh flowers always in readiness. The office of "herb-strewer to her Majesty the Queen" was continued as late as 1713, through the reign of Anne and almost into that of George I. The houses were very fragrant with flowers in pots and vases as well as with the rushes on the floor. Flowers were therefore very important features in house decoration. A Dutch traveler, Dr. Leminius, who visited England in 1560, was much struck by this and wrote: "Their chambers and parlors strewed over with sweet herbs refreshed me; their nosegays finely intermingled with sundry sorts of fragrant flowers in their bed-chambers and private rooms with comfortable smell cheered me up and entirely delighted all my senses." The Elizabethan lady was just as learned

in the medicinal properties of flowers and herbs as her Medieval

ancestor. "The housewife was the great ally of the doctor: in her still-room the lady with the ruff and farthingale was ever busy with the preparation of cordials, cooling waters, conserves of roses, spirits of herbs and juleps for calentures and fevers. All the herbs and flowers of the field and garden passed through her fair white hands. Poppy-water was good for weak stomachs; mint and rue-water was efficacious for the head and brain; and even walnuts yielded a cordial. Then there was cinnamon water and the essence of cloves, gilliflower and lemon water, sweet marjoram water and the spirit of ambergris. "These were the Elizabethan lady's

severer toils, besides acres of tapestry she had always on hand. "That wonderful still-room contains not only dried herbs and drugs, but gums, spices, ambergris, storax and cedar-bark, civet and dried flowers and roots. In that bowl angelica, carduus benedictus (Holy Thistle), betony, juniper-berries and wormwood are steeping to make a cordial-water for the young son about to travel; and yonder is oil of cloves, oil of nutmegs, oil of cinnamon, sugar, ambergris and musk, all mingling to form a quart of liquor as sweet as hypocras. Those scents and spices are for perfumed balls to be worn round the ladies' necks, there to move up and down to the music of sighs and heart-beating, envied by lovers whose letters will perhaps be perfumed by their contact. "What pleasant bright London gardens we dream of when we find that the remedy for a burning fever is honeysuckle leaves steeped in water, and that a cooling drink is composed of wood sorrel and Roman sorrel bruised and mixed with orange juice and barley-water. Mint is good for colic; conserves of roses for the tickling rheum; plaintain for flux; vervain for liver-complaint—all sound pleasanter than those strong biting minerals which now kill or cure and give nature no time to heal us in her own quiet way." EVOLUTION OF THE SHAKESPEARE GARDEN

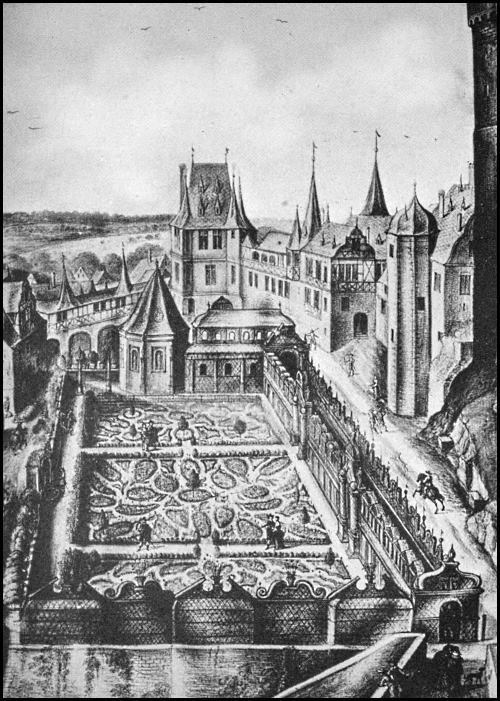

FIFTEENTH CENTURY GARDEN WITHIN CASTLE WALLS, FRENCH The Italian Renaissance Garden Consider the Renaissance garden of Italy on which the gardens that Shakespeare knew and loved were modeled. As described by Vernon Lee: "One great charm of Renaissance gardens was the skillful manner in which Nature and Art were blended together. The formal design of the Giardino segreto agreed with the straight lines of the house, and the walls with their clipped hedges led on to the wilder freer growth of woodland and meadow, while the dense shade of the bosco supplied an effective contrast to the sunny spaces of lawn and flower-bed. The ancient practice of cutting box-trees into fantastic shapes, known to the Romans as the topiary art, was largely restored in the Fifteenth Century and became an essential part of Italian gardens.

The Elizabethan flower garden as an independent garden came into existence about 1595. It was largely the creation of John Parkinson (1567-1650), who seems to have been the first person to insist that flowers were worthy of cultivation for their beauty quite apart from their value as medicinal herbs. Parkinson was also the first to make of equal importance the four enclosures of the period: (1) the garden of pleasant flowers; (2) the kitchen garden (herbs and roots); (3) the simples (medicinal); and (4) the orchard. Although published thirteen years after Shakespeare's death, Parkinson's book describes exactly the style of gardens and the variety of flowers that were familiar to Shakespeare; and to this book we may go with confidence to learn more intimately the aspect of what we may call the Shakespeare garden. In it we learn to our surprise that horticulture in the late Tudor and early Stuart days was not in the simple state that it is generally supposed to have been in. There were flower fanciers in and near London—and indeed throughout England—and there were expert gardeners and florists. Shakespeare very nearly follows order of perfume values in his selection of flowers to adorn the beautiful spot in the wood where Titania sleeps. Fairies were thought to be particularly fond of thyme; and it is for this reason that Shakespeare carpeted the bank with this sweet herb. Thyme is one of those plants which are particularly delightful if trodden upon and crushed. Shakespeare accordingly knew that the pressure of the Fairy Queen's little body upon the thyme would cause it to yield a delicious perfume. The Elizabethans, much more sensitive to perfume than we are to-day, appreciated the scent of what we consider lowly flowers. They did not hesitate to place a sprig of rosemary in a nosegay of choice flowers. They loved thyme, lavender, marjoram, mints, balm, and camomile, thinking that these herbs refreshed the head, stimulated the memory, and were antidotes against the plague. The flowers in the "knots" were perennials, planted so as to gain uniformity of height; and those that had affinity for one another were placed side by side. No attempt was made to group them; and no attempt was made to get masses of separate color and what we try for to-day. On the contrary, the Elizabethan gardener's idea was to mix and blend the flowers into a combination of varied hues that melted into one another as the hues of a rainbow blend and in such a way that at a distance no one could possibly tell what flowers produced this effect. This must have required much study on the part of the gardeners, who kept pace with the seasons and always had their beds in bloom. By the side of the showy and stately flowers, as well as in kitchen gardens, were grown the "herbs of grace" for culinary purposes and the medicinal herbs for "drams of poison." —"the cheerful Rosemary" was trained over arbors and permitted to run over mounds and banks as it pleased. Sir Thomas More allowed it to run all over his garden because the bees loved it and because it was the herb sacred to remembrance and friendship. In every garden the arbor was conspicuous. Sometimes it was a handsome little pavilion or summer-house; sometimes it was set into the hedge; sometimes it was cut out of the hedge in fantastic topiary work; sometimes it was made of lattice work; and[Pg 49] sometimes it was formed of upright or horizontal poles, over which roses, honeysuckle, or clematis (named also Lady's Bower because of this use) were trained. Whatever the framework was, plain or ornate, mattered but little; it was the creeper that counted, the trailing vines that gave character to the arbor, that gave delight to those who sought the arbor to rest during their stroll through the gardens, or to indulge in a pleasant chat, or delightful flirtation. A beautiful method of obtaining shady walks was to make a kind of continuous arbor or arcade of trees, trellises, and vines. This arcade was called poetically the "pleached alley." For the trees, willows, limes (lindens), and maples were used, and the vines were eglantine and other roses, honeysuckle (woodbine), clematis, rosemary, and grapevines. Pleaching means trimming the small branches and foliage of trees, or bushes, to bring them to a regular shape. Certain trees only are submissive to this treatment—holly, box, yew privet, whitethorn, hornbeam, linden, etc., to make arbors, hedges, bowers, colonnades and all cut-work. "Plashing is the half-cutting, or dividing of the quick growth almost to the outward bark and then laying it orderly in a slope manner as you see a cunning hedger lay a dead hedge and then with the smaller and more pliant branches to wreath and bind in the tops." Markham, "The County Farm" (London, 1616). Another feature of the garden was the maze, or labyrinth. It was a favorite diversion for a visitor to puzzle his way through the green walls, breast high, to the center. The labyrinth, or maze, was a fad of the day. It still exists in many English gardens that date from Elizabethan times and is a feature of many more recent gardens. Perhaps of all mazes the one at Hampton Court Palace is the most famous. The orchard was another feature of the Elizabethan garden. It was the custom for gentlemen to retire after dinner (which took place at eleven o'clock in the morning) to the garden arbor, or to the orchard, to partake of the "banquet" or dessert. THE "KNOTT GARDEN" The 'Knott Garden'—an enclosure which, being an invariable adjunct to every house of importance in Shakespeare's time, is the most essential part of the reconstruction, on Elizabethan lines, of the ground about New Place. "The whole is closely modeled on the designs and views shown in the contemporary books on gardening; and for every feature there is unimpeachable warrant. The enclosing palisade—a very favorite device of the Jacobean gardeners—oft Warwickshire oak, cleft, is exactly copied from the one in the famous tapestry of the 'Seven Deadly Sins' at Hampton Court. 'The garden is best to be square, encompassed on all four sides with a stately arched hedge, the arches on pillars of carpenter's work, of some 10 foot high, and 6 foot broad.' The 'tunnel,' or 'pleachéd bower, where honeysuckles, ripened by the sun, forbid the sun to enter'—follows ancient models, especially the one shown in the old contemporary picture in New Place Museum. "The dwarf wall, of old-fashioned bricks—hand-made, sun-dried, sand-finished, with occasional 'flarers,' laid in the Tudor bond, with wide mortar joints—is based on similar ones, still extant, of the period. The balustrade is identical, in its smallest details, with one figured in Didymus Mountain's 'Gardener's Labyrinth,' published in 1577—a book Shakespeare must certainly have consulted when laying out his own Knott Garden. The paths are to be of old stone from Wilmcote, the home of Shakespeare's mother. The intricate, interlacing patterns of the Knott beds—'the Knottes so enknotted it cannot be expressed,' as Cavendish says of Wolsey's garden—are taken, one from Mountain's book; two from Gervase Markham's 'Country Housewife's Garden' (1613); and one from William Lawson's 'New Orchard and Garden' (1618); and they are composed, as enjoined by those authorities, of box, thrift, lavender-cotton, and thyme, with their inter-spaces filled in with flowers." ROYAL ROSES FOR THE KNOTTED BEDS "In one point the Trustees have been able to 'go one better' than Shakespeare in his own 'curious knotted garden'—to use his own expression in 'Love's Labour's Lost.' For neither King James, nor his Queen, Anne of Denmark, nor Henry Prince of Wales sent him—so far as we know—any flowers for his garden. On his 356th birthday, however, there will be planted four old-fashioned English rose-trees—one in the center of each of the four 'knotted' beds—from King George, Queen Mary, Queen Alexandra, and the Prince of Wales. Surely Shakespeare, could he have known it, would have been touched by this tribute! "They will be planted by Lady Fairfax-Lucy, the heiress of Charlecote, and the direct lineal descendant of the Sir Thomas Lucy whose deer he is said to have poached, and who is supposed to have had him whipped for his offense, and who is believed to be satirized in the character of 'Justice Shallow.' This also might well have moved him! "Here, in the restored 'Knott Garden,' as everywhere in the grounds about New Place, flowers—Shakespeare's Flowers—will clothe and wreathe and perfume everything, all else being merely devised to set them off—musk-roses, climbing-roses, crab-apples, wild cherries, clematis, honeysuckle, sweetbriar, and many more.

|

||||||||